Women's Experiences of Re-offending and Rehabilitation

Executive Summary

This research was focused on the narratives of a group of women in New Zealand who had served sentences managed by the Department of Corrections, had received some form of rehabilitation, but nevertheless had re-offended. It sought to understand what women thought were important factors driving their re-offending, and how approaches to rehabilitative assistance could be improved to support desistance from crime. The study involved interviews with 54 women who were currently serving a prison sentence, had served at least one prior custodial or community sentence in the past six years, and had previously attended a rehabilitation programme.

Women's perceptions of the factors influencing their re-offending

A range of things 'went wrong' for the women which they identified as immediate precipitators of their offending:

- Relationships going wrong were often seen as an immediate trigger which led women back to offending. Relationships kept women stuck in cycles of offending through their return to families involved in crime, offending with partners, and offending to provide for family and partners. Relationships also created stress and trauma, for example, from domestic abuse, losing custody of children and family estrangement.

- Reliance on drugs, alcohol and gambling were seen as key drivers of their offending if they were stealing, or selling drugs in order to fund drug or gambling addictions, or if they offended while under the influence of alcohol or drugs. For others, substance abuse and addictions were seen to play a less direct role, for example, by contributing to wider instability that, together with other pressures, culminated in their re-offending.

- Economic pressures were frequently seen as a key trigger for re-offending. These included: financial stressors after release from prison, a desire for things they could not otherwise afford, and difficulties finding meaningful employment with limited job experience and criminal records.

- Women frequently returned to neighbourhoods where pro-social support networks and services were not readily available. They often did not have appropriate support when dealing with financial and emotional stress, and more easily fell back into crime.

While these situational triggers caused varying degrees of frustration and emotional instability, the issues these women faced are likely to be similar to those faced by other women who do not re-offend. Therefore, the ways women saw themselves and their past and current relationships, and the extent to which they felt equipped to deal with challenges, are likely to help explain why they re-offended.

Identity plays a key a role in the desistance process. Research literature on desistance from and persistence of offending shows that 'desisters' cease to hold the identity of an offender, instead regarding themselves in a pro-social light (Healy, 2013). In this study, unhelpful ways that women saw themselves (their identities) and their future prospects appeared to be shaped in two ways:

- Their sense of self was often influenced by their histories of poverty, trauma and crime; many felt trapped in cycles of offending, and so struggled to move past an offender identity.

- Their sense of self was also shaped by their gender identities reflected in roles as mothers, daughters and partners. They had a tendency to 'people please', prioritising relationship preservation, and the emotional and financial needs of others, above their own needs.

These identities created a range of tensions for women where meeting relationship responsibilities often took precedence over taking steps necessary to avoid reoffending.

The women in the study often felt they did not have the strategies to withstand situational triggers and setbacks without resorting to crime. In this study, the ways that women described their responses to the above challenges fell into two main categories:

- 'Spiralling down': crime was seen as the inevitable outcome of loss of control, an inability to cope in the face of emotional instability or external stressors; and

- 'Reverting to script': financial and relationship challenges led to conscious decisions to return to crime, regarded as offering a viable or, at times, the only means of meeting relationship and financial commitments, or achieving emotional equilibrium.

Within these narratives, the women revealed conflicting perceptions over the extent to which they felt able to desist from crime. Those in the 'spiral down' group perceived themselves as having little or no control over their situation or their emotional responses in the face of insurmountable problems. Those in the 'revert to script' group described their decisions differently; offending was perceived as logical, a means of addressing financial hardship and relationship commitments, and meeting the emotional need to 'feel OK'. Such choices were compounded by feelings of powerlessness, the perceived absence of other means of meeting immediate needs.

Women's perceptions of their rehabilitation

The female offenders interviewed had had access to a range of rehabilitation programmes and services while serving sentences either in the community or in prison. Overall they valued these opportunities, but frequently stated that their needs were not adequately met. The women identified the following as important to enhancing their rehabilitation and reintegration experiences:

- A respectful and engaging experience: being consulted by staff on their own perceptions of what they needed; being informed about what programmes were available; having a voice in decisions about the programmes they were referred to; having progress positively acknowledged.

- Interventions that were tailored to meet multiple relevant needs: not treating specific needs in isolation, but addressing emotional, practical, addiction and support-related needs concurrently through a single programme or a combination of programmes and services.

- Help to understand the underlying drivers of their offending: obtaining insight into past experiences and how these may have shaped their offending, allowing opportunity to face and deal with past experiences of trauma.

- Support to build a positive self-identity, self-esteem and emotional resilience: gaining confidence in their abilities to cope, obtaining the 'tools and techniques' to break cycles of offending; this was particularly salient in the area of relationships, where women saw a strong need to both recognise and deal with unhealthy interpersonal relationships, as well as build positive relationships with partners, family and children.

- On-going emotional support: someone to talk to in the community to provide support and guidance in managing difficulties, and reinforcing the desire to stay offence-free. Immediate post-sentence support, as well as longer-term support networks in the community were both seen as valuable.

Recommendations for approaches to women's rehabilitation

- Case management of female offenders should be a respectful and motivating process where women's opinions about their needs and rehabilitation preferences are listened to, and where there is clear communication from staff to offenders about available programmes and services.

- There is an individualised approach to each woman's rehabilitation where women are assigned to programmes and services which simultaneously address their unique combinations of needs. This may mean wider access to offence-focused programmes such as Kowhiritanga, or access to a wider range of addictions services and community programmes.

- Access to specialist offence-focused programmes such as Kowhiritanga especially for those on dishonesty and burglary charges and/or those serving short sentences and community sentences.

- A focus on building self-esteem and self-efficacy across programmes and services, as well as the development of strategies for managing anger, and other emotions.

- There is increased access to violence programmes, which address women's experiences as both victims and perpetrators of violence. More women should be aware of services to address past experiences of victimisation, such as ACC counselling.

- Rehabilitation programmes recognise that relationships with partners, children and family play a key role in women's lives, and are often pivotal in relapses into re-offending; consequently, conflict resolution skills, and support for managing relationships, are critical.

- Preparing women for employment in the community is done in a way that provides them with both practical skills and the confidence to seek employment. This means ensuring access to training and job placements in a range of areas, especially Release to Work opportunities; access to job seeking skills and 'careers counsellors'; and where necessary, efforts to build women's confidence to seek work if they have a history of unemployment.

- Women have access to an emotional support service during their sentence and post-sentence. This could include access to counselling services, mentorship relationships or service providers who can provide long-term emotional support.

- Rehabilitation and reintegration services help women to build long-term pro-social support networks to ensure this support can continue. This could include facilitating links to service providers, community groups or their children's schools.

Background

International research has shown that the pathways women take into offending can differ in significant ways to those of men. Although poverty, peer influences, parental neglect, families with criminal associations and impulsive personality traits are influential factors for both men and women, 'female specific' factors also influence women's entry into crime and continued offending. Chief amongst these are higher rates of physical and sexual victimisation, intimate partner relationships with offenders, the stresses associated with parenting and child custody processes, mental health issues, substance abuse, and financial pressures (Giordano et al., 2006; Kruttschnitt , 2003; Van Voorhis et al., 2010). It is now generally accepted that women should have access to 'gender-responsive programming and treatment' to adequately address offending-related needs (Wattanaporn and Holtfreter, 2014).

Research on Women's Pathways into Crime and Re-Offending

A 1999 study carried out on the needs areas of female offenders in New Zealand (Moth and Hudson, 1999) found that the majority of women had committed their first offence before 16 years of age. As already outlined, many reported significant mental health issues, and past experiences of abuse (particularly sexual abuse) as children. Many of the women also had current difficulties in intimate partner relationships, and challenges raising children, and experiences of poor self-esteem and chronically low mood. Also noted however were characteristics common to male offenders: behavioural and academic problems at school, chronic unemployment, poor job skills, frequent drug use, financial problems, accommodation difficulties and an absence of pro-social supports. The Moth report recommended that further research be conducted investigating the links between the needs areas identified and offending patterns in order to increase knowledge of 'which variables are related to the risk of re-offending, as well as our understanding of the processes involved and what to target by way of interventions designed to reduce risk' (Moth and Hudson, 1999).

Research on specific factors understood to influence women's entry into crime and continued offending are briefly discussed below. The majority of these studies are from the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia.

Family dysfunction

Female offenders frequently have dysfunctional families of origin. Common amongst such families are parental criminal involvement, marital conflict and abuse, parental drug and alcohol abuse, and parental neglect (Belknap, 2007; Giordano et al., 2006). These childhood experiences leave a legacy of trauma and emotional dysregulation, including chronic anger (King & Gibbs, 2002; Morash, 2010). 'Criminal learning' is also a consequence (Giordano et al., 2006).

Childhood victimisation

The majority of studies on female offenders show that high numbers have experienced sexual and/or physical abuse as children or adolescents (Belknap, 2007; McIvor, 2008; Sharpe, 2012; Belknap & Holsinger, 2006; Severson et al., 2007; Taylor, 2004). Such victimisation has known links to negative psychological and behavioural outcomes such as mental illness and substance dependence (Brennan et al., 2012; Taylor, 2004; Wattanaporn, 2014). These can act as precipitating factors to offending, with a common pathway involving girls running away to escape abuse, using drugs and alcohol to cope and then committing theft in order to sustain drugs and alcohol use (Sharpe, 2012; Taylor, 2004; Giordano et al., 2006).

Abusive Partner Relationships

Female offenders often find themselves involved in abusive relationships with partners and subject to violence and emotional dominance and control (McIvor, 2008). Such relationships, especially when the partner is an offender, have been highlighted in a number of studies as directly linked to the women's own offending (King & Gibbs, 2002; Giordano et al., 2006; Taylor, 2004). Brennan et al.'s (2012) study found that dysfunctional intimate relationships eroded women's self-sufficiency and precipitated depression, anxiety and substance abuse, as well as adult victimisation. Female offenders are also more likely than male offenders to re-engage in crime as a means of retaining a partner who is an active offender (Barry, 2007).

Parenting difficulties

The challenges associated with parenting are frequently highlighted in studies of re-offending amongst females. Common stressors include the tensions and feelings of loss associated with losing custody of children and/or attempts to retain or regain custody (Opsal & Foley, 2013; Shechon & Flynn, 2007; Morash, 2010; Huebner et al., 2010). Such stressors appear to decrease women's chances of desistance (Opsal & Foley, 2013).

Mental Health

Common to many female offenders are problems such as depression and anxiety, often stemming from previous trauma and victimisation (McIvor, 2008; Brennan et al., 2012; Taylor, 2004; Blanchetter and Brown, 2007; Van Voorish et al., 2010; Salisbury and Van Voorhis, 2009). Low self-esteem and a lack of confidence are also often reported in female offender populations (Belknap & Holsinger, 2006; Blanchetter & Brown, 2007). Studies on women offenders' reintegration have found that mental health issues make get employment difficult (Opsal & Foley, 2013; Leverntz, 2006; Huebner et al., 2010).

Drugs and alcohol

Substance abuse is a common factor in the entry into crime for many women (Morash, 2010; Sharpe, 2012; King & Gibbs, 2012; Brennan et al., 2012; Blanchette & Brown, 2007; Severson et al., 2012). Substance abuse by female offenders is a means of coping with neglect/abuse (Sharpe, 2012). Once initiated into drug use, sometimes by male partners, many female offenders report having committed crime to finance drug habits (McIvor, 2008; Daly, 1994; Barry, 2007). Property and dishonesty-type crimes are often related to drug and alcohol use (Morash, 2009). Substance abuse problems also subsequently limit chances of obtaining employment, re-building relationships with children or receiving social support, which makes re-offending more likely (Huebner et al., 2010; Cobbina, 2010).

Education and Employment

Limited educational attainment and broader problems at school have been linked to offending (Wattanaporn & Holtfreter, 2014; Sharpe, 2012; Belknap, 2007; Van Voorhis, 2010). Low educational attainment often leads to limited employment opportunities. Women released from prison often struggle to find employment (Morash, 2010; Opsal and Foley, 2013; Spjeldnes et al., 2009). Resulting money pressures can influence the likelihood of re-offending (Opsal & Foley, 2013; Boober et al., 2011).

Accommodation

Women face particular difficulty in finding suitable housing, especially if they also have children (McPherson, 2007; Morash, 2010; Opsal & Foley, 2012). This specific factor can increase the likelihood of their returning to unsafe environments, such as living with abusive partners. Neighbourhood also affects the likelihood of re-offending to the degree to which anti-social relationships are further fostered (Huebner et al., 2010).

Identity and Desistance

Research suggests that the difference between those who desist and those who do not can hinge on what is sometimes described as 'internal transformation'. Desisters have been shown to have higher levels of self-efficacy, personal resilience and more effective coping strategies (Doherty, 2004; Healy, 2013; LeBel et al., 2011). Interviews with successful desisters suggests that there is often a new identity formed, as an 'ordinary citizen', which distances themselves from the 'offender' identity (Healy, 2013; Doherty et al., 2004). Those who persist on the other hand internalise the label of 'offender' and find it very difficult to construct a different identify (LeBel et al., 2011). They also lack a sense of personal agency and perceive that their lives are determined by childhood experiences, or stigma and shame (LeBel et al., 2011). Healy (2013) found that persisters described feeling powerless in the face of their problems and their lack of resources, and had little hope for the future.

Unable to envisage any meaningful alternative to crime, they felt trapped by their circumstances and believed they were unable to resist the temptation to offend … they were following a 'default route' to adulthood.

Desisters and persisters are often faced with the same obstacles, but persisters' negative emotional state prevents them from hooking into positive non-criminogenic opportunities that may exist (Healy, 2013).

In summary, a number of important characteristics are known to be associated with female offending. Correctional rehabilitation personnel need to take such factors into consideration when designing gender-responsive programmes and services.

Research Methodology

Aims

The current study focused on women's experiences of re-offending despite having completed some form of rehabilitation. The study explored women's perspectives on what caused them to re-offend following completion of community and/or custodial sentences and the extent to which Department programmes they had taken part in had helped them. The research aims to better understand ways in which women found their rehabilitation interventions useful, including the extent to which interventions were perceived as relevant to issues they believe influenced continued offending. It is hoped that findings will enable the Department to improve the support it provides to women, and thereby to improve effectiveness of rehabilitation. The study employs a qualitative methodology.

The study was based on interviews with 54 women currently serving a prison sentence in one of the three New Zealand women's prisons. These women had served at least one prior custodial or community sentence within the past six years. They also needed to have attended some form of rehabilitation programme during the prior sentence.

A list of women meeting the first two criteria was generated and the records of these held in the Integrated Offender Management System (IOMS) were analysed to identify whether they participated in rehabilitative interventions while on a community or custodial sentence in the past six years. Eligible programmes and services were those designed to target their criminogenic needs (see Appendix One for details). Women who commenced, but did not complete, programmes were included. Women were also asked about any training/education/work they completed in prison, although this was not part of the eligibility criteria and was not the focus of the research.

Eliciting participation in the research

Eighty-two potential participants were identified and prison staff provided all of them with an information sheet about the research and a consent form. Sixty five agreed at this stage to be interviewed. Maori women were given the option of being interviewed by a Maori researcher. Interviews were planned with those who indicated a willingness to contribute to the research. Before the interview commenced, the purpose of the research was explained and women were given the opportunity to re-confirm their consent to participate in the research (and be interviewed) or decline their consent, at which point the interview was terminated.

Ethics

All participants in the research were informed of its purpose, why they were selected and how the information would be used. They were assured that they would not be identified, that any information they provided would be reported in a manner that could not be used to identify them as individuals. They were advised that they could withdraw from the research (and their interview records destroyed) within two weeks following their interview.

Interviews

A semi-structured interview guide (Appendix D) was designed to explore the women's perspectives; separate sections focused on the programmes they received on their past sentence(s); the factors influencing their most recent re-offending; and the extent to which they thought programmes helped them post-completion of their sentence. They were also asked about the perceived usefulness of the rehabilitation programmes they were currently taking part in. Interviews were completed from 9 December 2014 to 24 February 2015 by Marianne Bevan, a Research Advisor with the Department of Corrections and Nan Wehipeihana, an independent research consultant.

Analysis

The researchers took detailed notes during the interviews and, with participants' permission, recorded each interview. The majority of interviews were transcribed for analysis. All data was thematically coded and analysed. Pseudonyms are used for the women in order to personalise their accounts.

Limitations

The research sought to better understand what women perceived to have been the drivers of their re-offending. It was not intended to specify the causes or drivers of females' offending in a way that might be generalisable across the female offender population, and should not be read as such. Instead, it is an exploration into some women's perceptions of their re-offending and rehabilitation. It was designed to provide insights into how rehabilitation programmes may be better tailored to the needs of female offenders generally. A qualitative methodology was most useful as it allowed us to gather the information needed to accurately represent these women's understandings of their re-offending and treatment. This approach allowed women's re-offending to be explored in its totality; that is, for us to investigate the role various needs factors played in the unfolding offending process, and for the relationship between different needs factors to be explored. It allowed us to explore in more detail the realities of these women's lives, the contexts of their offending and the differences and similarities in their re-offending, and what this may mean for ensuring that rehabilitation can be tailored to the unique needs of each woman.

With the exception of community-based alcohol and other drug (AoD) counselling which had a high attendance rate, the majority of rehabilitation programmes had been attended by small numbers of people. The research therefore should not interpreted as an evaluation of any particular rehabilitation programme. Rather, it is a commentary of women who have accessed programmes and whether these experiences met their own perceived needs, and why this may have been be the case. It aims to paint picture of the broader approaches to rehabilitation women valued.

Female offenders in New Zealand

Women make up a lesser proportion of the offender population in New Zealand. As at June 30 2014, women comprised six percent of the custodial population, and 20 percent of the community population (Department of Corrections, 2014). The characteristics of both the general female offender population and the research cohort are discussed below.

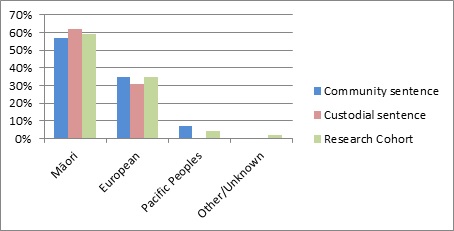

Ethnicity

Maori women are over represented in the offending population; 62 percent of women serving custodial sentences and 57 percent of women with community sentences are Maori. This disproportionality was reflected in the research cohort.

Graph 1 Ethnicity of general female offender population and research cohort

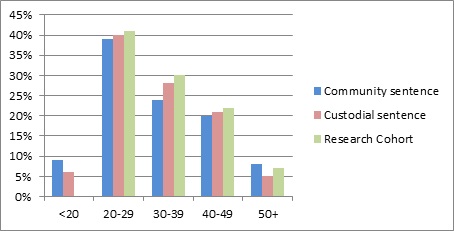

Age

Nearly two fifths of women serving custodial or community sentences (40 percent and 39 percent) are aged 20 - 29; and around a quarter are aged 30 - 39. The research cohort was slightly older on average than the general population of female offenders.

Graph 2 Age at sentencing for general female offender population and research cohort

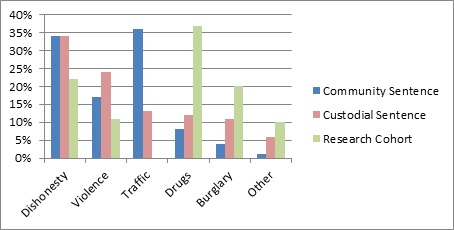

Offence and sentences types

Of the 665 custodial sentences started by women in 2014, the most common most serious offence was dishonesty, whereas for the research cohort, it was drugs.

Graph 3 Most common serious offence by sentence type for general female offender population and research cohort

Re-offending

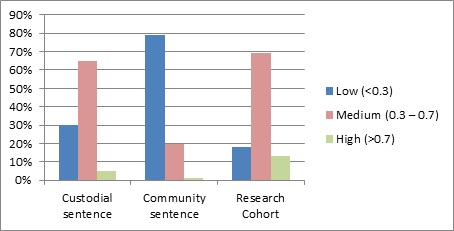

At 14.6 percent within 12 months of release, women have a lower re-imprisonment rate (27.8 percent for men). Reconviction rates amongst those on community sentences (19.2 percent, vs 28.6 percent) are also lower than found for men. In the wider female offender population, over half (53 percent) serving a custodial sentence have served a previous custodial sentence. Within the research cohort, the majority of women (76 percent) had served a previous custodial sentence.

Women's risk of re-offending (Roc*RoI)1 is outlined in the table below. There was a higher proportion of medium and high risk women in the research cohort compared to the general female prison population. This is to be expected, as the women in the research cohort were selected on the basis of an established having a history of conviction and sentencing.

Graph 4 Risk of reoffending for general female offender population and research cohort

Research Findings

Women's perceptions of the factors influencing their re-offending

This chapter of the report describes the beliefs, behaviours and circumstances that women believed led to their re-offending. Findings are presented in two sections, reflecting what emerged as relatively distinct domains: 'Internal Factors' and 'Situational Factors', as outlined below.

Internal Factors

The first two sub-sections introduce concepts that will be used throughout the report to explore how women saw themselves and their future prospects (their self identities). This includes the way they use their history to explain their current experiences, the idea of themselves as trapped in 'offender identities' and as 'people pleasers'.

The second explores how women's sense of self affected their perceived ability to desist from crime. The concepts of 'spiral down' and 'revert to script' are used to show the two common patterns of how women responded to challenges. This section shows how their perceived levels of agency affected how they responded to challenges.

Situational factors

The remaining sub-section discusses how four situational factors - relationships, addictions and substance abuse, economic pressures and limited social support - played out as direct triggers for re-offending. It also explores how internal factors interacted with the situational to influenced women's responses to challenges, and expands on how the two re-offending pathways played out.

Internal Factors

Using the past to make sense of the present

A range of life circumstances were discussed when women described their offending. Some described growing up in institutional care with little or no family involvement. Many had grown up in families with gang involvement, crime and drug use. Others described family dysfunction and traumatic experiences, including witnessing or experiencing sexual, physical and psychological abuse. Some of the women had relatively stable upbringings/families but had experiences that they considered traumatic, such as sexual abuse, or a parent with mental illness or addictions. A much smaller number described 'good' backgrounds with loving, supportive families. Women also described a range of other significant life experiences such as their own addictions, deaths of family and friends, family conflicts, and damaging and abusive relationships.

Relationship Identities: 'People pleasing' and 'soldiering on'

Research on the desistance and persistence of offending has frequently shown that 'identity' - how the individual views and 'labels' herself - plays a role in offending persistence and desistance. Being able to discard an identity as 'an offender', and conceive of themselves as a pro-social person, can be a crucial step towards desistance (Healy, 2013). The existence of an 'offender identity' was visible within the narratives of many of the women, which will be elaborated on in latter sections. However, in this study, past and current relationships also appeared to play an important role in shaping women's sense of identity. Identities were often tied up with being daughters, sisters, partners and mothers, and how these 'relationship identities' were enacted and prioritised affected their ability to leave behind an offender identity.

'People pleasers'

The notion of being a 'people pleaser' and having a lack of boundaries in relationships was a behaviour that women commonly identified which influenced how they interacted with others and behaved in relationships. Women described feeling pressure to act in ways that kept others around them happy. Several stated they routinely accepted responsibility for parents, children, siblings and partners, both in terms of emotional well-being as well as materially and financially.

A typical example is illustrated in this quote by Sophie, a Maori woman in her 30s who said:

I've never put boundaries in place … I'm the people pleaser, I like to help people but I never have enough time and energy for myself, all my time is as the problem-solver, the people pleaser for everyone else … but who's more important? It's myself.

Another woman stated, 'you know a lot of my problem has been that I've lived my life for someone else'. Women described having learnt these behaviours through their past experiences - for example, through seeing their mothers behave in that way, or through feeling that (as an adolescent) they had to hold the family together when parents were absent or incapable of providing proper parenting.

'People pleasing' behaviour was also mentioned as featuring in periods leading up to their offending. This included situations where they felt obliged or pressured to take care of parents or siblings who were not coping on their own, or taking on financial responsibility for a partner. Tracey, a European woman in her 40s, described such a scenario: 'I had too many people leaning on me. It wasn't worth being a people pleaser because look who's doing the sentence now'. For some, a sense of low self-worth seemed implicated in the belief that others' wants and needs were more important than their own.

'Soldiering on'

Women also spoke of the felt need to suppress their own emotional reactions and needs and instead to simply 'soldier on'. Part of this was related to wanting to appear in control of situations. Also described was the tendency to 'bottle emotions'; instead of giving expression to feelings of helplessness, anger or frustration, it was necessary (as one woman described it) to put on a 'brave face'. The following quote by Rachel, a Maori woman in her 20s illustrates this:

A lot of the time when things are getting hard for me, if I'm not getting help I don't really reach out and ask for it. I just suck it in, soldier on and keep going. But that ['soldiering on'] I learnt could be traced back to mum … she was like that too.

As will be elaborated on throughout this report, these identities and behaviours tended to create a range of tensions for women, often centred on conflicting imperatives of relationships responsibilities versus exiting a criminal lifestyle. This included tensions between trying to distance themselves from criminal associates while being drawn into taking care of family members who were criminally active; trying to manage their own emotional and physical needs while feeling pressured to prioritise the emotional and physical needs of others; trying to be good mothers to their children while feeling that their criminal pasts precluded this. Conflict between such imperatives was experienced by many of the women as central to their continued offending.

Agency and Emotional Resilience: 'Spiralling Down' and 'Reverting to Script'

Studies on offending desistance have shown that those who desist tend to exhibit higher levels of two key attributes: self-efficacy, and resilience. LeBel et al. (2008) suggests that the common thread is 'hope': desire for a particular outcome, and belief that the individual has the capacity to make it happen, come what may. Attempting to desist from crime almost inevitably presents minor and major challenges. Resilience often comes down to possessing skills and strategies to cope, and to moderate the associated emotional distress (Rumgay, 2004).

Two main dysfunctional 'pathways' characterised how women in this study reported responding to personal and interpersonal difficulties, making re-offending more likely:

- 'Spiralling down': crime was is seen as the inevitable outcome of loss of control, an inability to cope in the face of emotional instability or external stressors; and

- 'Reverting to script': financial and relationship challenges led to conscious decisions to return to crime, regarded as offering a viable or, at times, the only means of meeting relationship and financial commitments, or achieving emotional equilibrium.

'Spiral Down'

Many of the women described a similar trajectory leading to offending which was a kind of 'spiral down' (or 'snapping') in response to shocks and challenges. There was usually a strong perception of losing control, of 'everything unravelling'. Being overwhelmed by emotions was experienced not only as a precursor to re-offending, but a state in which life problems were further compounded, and personal change seemed unattainable. More often than not, recourse to alcohol and drug abuse or, less frequently, gambling habits, accompanied this state of feeling out of control.

For some women, traumatic events triggered the downward spiral. Amiria, a Mâori woman in her 40s, described the murder of her mother as precipitating the resumption of a gambling addiction which rapidly led to thefts. As she explained:

Things got hard around 6 months before coming into jail. My mum died, she was murdered. I didn't even know my mum. I don't love my mum but I had to bury her by myself and I just went downhill from there, and gambling and I didn't know who to reach out, to say 'fuck, help me, I'm going down', sinking and sinking and, yip, it was too late, I did my crimes.

Thus, crime was the end result of a sense of loss of control, as she 'sank' under the emotional fallout of her mother's death.

The majority of women in this category described their offending as following on from a period of emotional turmoil. This state typically arose as women sought to respond to demands put upon them from multiple sources, in a context where material or emotional support from others was largely absent. Many described a sense of 'snapping' under stress, which sometime resulted in violent acts or damaging property. The case of Rachel, a Maori woman in her 20s, was illustrative: released from prison after serving a sentence for violence, Rachel found herself to be practically the sole caregiver for her mother, who had a terminal illness. She also maintained some contact with her father, but the relationship was 'tense'. Simultaneously she was in what she described as 'a bad relationship' with a partner. Social time was occasionally spent with drug-using associates. Feeling acutely stressed over her responsibilities particularly to her mother, and with no-one to talk to about it, she described the outcome: 'I don't know … I just jumped in my car and went, and I ran someone over. It was like build up, build up, and I just snapped.'

Isolation and loneliness in many cases compounded feelings of low self-esteem and even worthlessness, which for some quickened the downward spiral. For example, Kate, a European woman in her 40s, had recently left an abusive relationship and given up custody of her children. Despite being in an alcohol rehabilitation programme she reports feeling isolated and alone. A lapse back into alcohol abuse quickly led to a crime of violence. As she explained:

There'd been a death and I'd left rehab to go to the funeral (but) things were imploding for me and I didn't really know who to go to. I didn't really feel like I fitted in anywhere anymore…I was in a, for me, a desperate space, I was feeling really stressed, really pressured, really angry and frustrated and upset…

A number of the women with 'spiral down' patterns of relapse acknowledged that problems with controlling anger and violence exacerbated their situation. As a result, relationship break-ups, or on-going abusive relationships, were triggers for worsening conflict and unhappiness, and the creation of added stressors and difficulties, such as loss of accommodation.

In summary, women in this group viewed themselves as reaching a point where they had lost control. The resulting offending was thus seldom felt to be a conscious decision, but the end point in a process of the unravelling and disarray of their lives at that point. Lacking any strategies to manage or contain the challenges thrown up at them, crime was the result.

'Revert to script'

A second broad sub-group of women described their offending as simply resumption or return to old and established patterns of behaviour. Offending was described mostly as a conscious decision, a way to deal with difficult circumstances, or to meet material or emotional needs.

It needs to be first mentioned however that a small number of women in the study openly acknowledged that they had not (at the time of re-offending) ever previously considered or wanted to change their behaviour. These individuals either could not envisage another lifestyle different to one based around crime, or they perceived that the benefits of their current lifestyle outweighed the expected benefits of becoming law-abiding. This was particularly noticeable amongst those whose offending involved sale and supply of drugs. For example, Kaylee knew no other way of making money as readily as through drug dealing. As she explained, 'it was just the way I knew how to make money'. Selling drugs was, for her, not 'really' a crime, not something that hurt or damaged other people. A few others acknowledged relishing the standard of lifestyle that, as far as they knew, only criminal activity could support.

Balancing financial and relationship needs

In contrast, a significant number of the women had made earnest decisions to desist from crime, but were subsequently unable to maintain the commitment. For many, financial troubles, mainly in the period shortly after prison, were the major hurdle. Crime tended to be rationalised as the only way to meet their own needs or the needs of children, family and partners. Some described it as economic necessity, while others described simply liking being able to buy things for themselves and their families that would otherwise be financially out of reach.

The search for a pro-social self amidst cycles of crime

A significant proportion of the women interviewed described being 'trapped' in offending lifestyles. Although there might be offence-free period of their lives, challenges or difficulties in their personal and social circumstances often led to the familiar pattern re-emerging. The experience of Mere, a Maori woman in her 30s with a history of shoplifting offences, was illustrative of this. Mere described her situation as follows: 'I'm stuck in that cycle where it's hard to get out or I don't know how to get out because I'm not shown any different way or any other way because I've always been on the same track.' When she was released from prison she felt a desire to go straight but when financial hardship arose, compounded by family conflict, she 'did not know how to cope':

My mother-in-law took over my house and … boom … 'now you can pay for the rent' and all that stuff - I was bombarded with a whole lot of family issues, my kids and stuff like that. So it was just back to the same old cycle again. I tried to do it better but it didn't work. I (had) thought 'this time I'm going to do it, I can do it', you know, but then next minute something just goes wrong like the landlord come over and say I need these arrears in full, and the power gets turned off so it's all those stresses and not knowing where to go (for money).

In many of these narratives there was a sense of powerlessness and inevitability. Patterns of offending had usually started at a young age and, in the face of adversity, the women reverted to established patterns.

Some women described that re-offending, being caught, and then being sent to prison had a sense of inevitability. Tui, a Maori woman in her 20s, explained that 'I have this real bad thing - something bad happens in my life, and I just don't care any more … I'm going back to jail'. Casey, a European woman in her 30s, also epitomised this view of her drug dealing:

I knew the ultimate price would be prison, nothing's going to make it hit home until I came to prison. I knew I was going to get caught, it was just a matter of time, I knew the consequences but I just didn't care … oh well, I did care it was just mixed … like somebody save me, but how?

Accompanying this fatalistic outlook was a lack of self-efficacy. Accompanied by low confidence and self-esteem, these women regarded crime as the only effective thing they were capable of. Waimarie, a Mâori woman in her 40s with a long history of dishonesty offending described her negative self-perception thus: '… you feel like you can't do anything else but steal'. Many of the women spoke in ways suggesting limited confidence in their ability to desist from further criminal activity.

Emotional reward

A subset of women spoke of their offending in terms that suggested the behaviour generated some kind of emotional reward. Some even described getting a 'thrill' from offending. There was an element of pride in the ability to 'beat the system' and successfully pull off certain types of crimes. Others however spoke in terms that suggested compulsive or even addictive behaviour, temptations which they struggled against but found difficult to resist. Waimarie's long history of dishonesty offending was described as driven not only by 'need' but also feelings of compulsion. Against a backdrop of personal struggles and crises (including attempted suicide) she found that stealing made her feel 'normal':

Stealing again made me feel normal, I started feeling myself again … I know it's all up in your mind and you can just say no but we just get this feeling like an adrenalin rush … It does make you feel good although there's a lot of times it makes you feel guilty.

This pattern of returning to crime, getting a 'thrill' from it but also 'feeling like ones normal self' suggests that crime can become central to some women's sense of identity. Crime is not just a perceived 'resort' from pressure, but an activity that brings a sense of normalcy, stability, and distraction from chronic problems and stress. Described as the 'affective connections to crime', some researchers suggest that committing crime can both alleviate negative emotions while simultaneously generating positive emotions such as excitement (e.g., Giordano et al., 2007).

On the other hand, a number of women who had committed dishonesty and burglary offences described stealing as a kind of addiction, something which was very difficult to stop because it felt compulsive. Some described themselves as 'addicted' to stealing, often being individuals who had other addictions such as to alcohol, drugs or gambling. Tui's explanation of her shoplifting was evidence of this: 'it's like an addiction … I just can't help it. It's an impulsive reaction, you know: think about it, do it. Yeah, that is much more of a disease for me than gambling or drinking'. Tui had a history of drug use but described shoplifting as her 'main' addiction. She said at points she became so frustrated with the compulsive feelings about shoplifting that she increased her drug use to suppress the urges. Another with a long history of dishonesty said when she got out of prison she managed to stop stealing, but only by replacing it with gambling which she then got addicted to - and then resumed shoplifting to fund the new gambling habit.

Summary

The majority of women wanted to desist from crime. However, within these narratives, there were conflicting feelings about the extent to which desistance was desirable or possible. Those in the 'spiral down' group perceived themselves to have limited control over their situations and emotional responses in the face of challenges. Those in the 'revert to script' group described their decisions differently; offending was described more as a rational decision made within the context of having limited financial resources, pressing relationship commitments, and the continuing pull and allure of crime. Therefore while many women had a genuine desire to desist, they often did not have the belief that this was possible in the context of their past experiences and current relationship commitments, nor the strategies to put this in place and deal with setbacks.

Situational Factors

The following sections discuss relationships, addictions, financial circumstances and social supports in the context of these acting as 'triggers' for offending in either 'spiral down' or 'revert to script' scenarios.

Relationships and Roles

Relationship conflict and breakdown - with family, partners, children and friends - was a frequent trigger to re-offending. Relationships also served to keep some women 'stuck' in cycles of offending.

Family of origin2

Many women were estranged in some way from their families of origin or had only tenuous connections to them. Some women in this group were motivated to renew or improve these relationships. Other women were still closely connected to families, and some reported their families as being a source of regular emotional and practical support. Nevertheless, for many women, family relationships were often implicated in their re- offending cycles. For a proportion of those interviewed, returning to the family of origin meant being re-absorbed into old patterns of established familial behaviour, such as drug use and gang involvement. Mere, a Māori woman in her 30s typified these complex relationships. Her entire family was gang-involved, and she had frequently offended in the company of her sister. She recognised the challenge of stopping offending while remaining connected to her family:

Same thing that I'd been growing up with all my life … gangs are my family. We're all tight-knit … but moving back to that means moving back to negatives and hardly any positives, just back to the same cycle.

Multiple factors kept women tied to problematic family relationships. Not uncommon was the burden of responsibility for taking care of particular family members such as a chronically ill parent. For others, the alternatives to stressful or unhelpful family relationships were worse: moving back to an abusive relationship, moving in with criminally active associates, or living in unsafe housing.

Family conflicts also acted as a trigger to offending, often following periods of stress and drama, and escalating alcohol and drug use. Many were estranged from one or more other family members, and trying to re-build relationships was often a fraught process. Grace, a European woman in her 40s with a history of drug and dishonesty offending was an example of this. Though estranged from her family, she had enjoyed several years of being offence-free. At a particular stage she sought to repair relationships with certain family members, but was completely rebuffed. This overt rejection triggered a return to drug use, a renewed drug habit, and ultimately to supplying drugs to others to fund her own use.

Emotional impacts from common intra-familial strife and conflict were also often a trigger. Karly, a European woman in her 20s, had recently left an abusive relationship, was in financial strife, and had lost her accommodation. She described a typical 'spiral down' response, accompanied by renewed drug and alcohol use. Against this backdrop, chronic difficulties in her relationship with her mother flared again, resulting in an emotional melt- down. She recalls the scene of trying to pack up and leave her house:

(I was) so angry and frustrated because my mum was putting pressure on me to start packing, you know 'hurry up you've got a certain amount of time to get out' … frustrating me, her coming into the picture … I just wanted to have time out.

She subsequently set fire to her house in what she acknowledged was an 'over-reaction' committed in a moment of anger.

Partners

A few women described enjoying supportive intimate relationships, with partners providing support with children, emotional and financial support, and stability. However, the majority of the women who had had recent relationships described them as exploitative, abusive or in a range of other ways unsatisfactory. Being in, or the process of exiting such relationships tended to be emotionally traumatic, leading to personal instability. In many cases their own emotional states we exacerbated by a return to drug and alcohol use. This was evident in a classic 'spiral down' by Alexis, a European woman in her 20s, who stated that every relationship she had ever had involved her feeling as though she was a 'piece of meat'. After a series of unsatisfactory relationships with older men, she went through a period on her own and became offence-free for several years. A new relationship with an older man quickly became abusive once more, to which she responded by drinking heavily. Arrested for drink-driving, she then breached her bail conditions in order to get away from her partner.

For others, trauma and anger associated with abusive relationships led to acting out violently or in destruction of property. For example, Karly described the harms the relationship had inflicted on her as follows:

I'm pretty sure everything was to do with [partner] … I don't know what exactly had happened with our relationship but I think what he was doing to me I was taking out on other people … I couldn't get out of the relationship myself because he was so abusive to me.

Others of the women described relationships which were not overtly abusive but where they received no support (either financial or emotional) from partners, thus having to manage household responsibilities, including for children) entirely on their own.

A significant number of the women had entered relationships with partners who were active offenders and/or drug users. As a result, some of these women had been imprisoned for offences committed with their (then) partner. This was the case for Raven, who had a history of burglary offending. Raven described leaving prison with hopeful intentions of going straight, obtaining a house and securing custody of her children. However, within a short time thereafter she had formed a relationship with a man who was a prolific burglar, which led to her 'easily slipping back' into her former behaviour.

Being in a relationship with a drug-dependent partner was also a path back into trouble. This usually came about as a result of committing crimes to support their own habit and the partner's habits. Alternatively, drug-abusing partners seldom contributed anything to household costs or childcare, spending whatever income they had on alcohol, drugs or other addictions. Their female partner then explained their own offending as the only viable way to pay for household expenses. Casey explained that:

Once they died [aunt and uncle] I was left with her [her daughter] and it was hard trying to feed her. My partner at the time, my daughter's father, he was so hopeless he never got a job, lived off my benefit, 'cause I was on the DPB … I had to pay for the rent, the power while he was out pissing his money against the wall.

Children

A majority of women interviewed had care of children at the time of their offending. Children were generally felt to be a positive thing in the lives of these women, and many spoke of the fact that the desire to give their children a better life was an incentive for desisting from crime. However, for some, parenting created multiple difficulties, especially financial pressure, and some said that providing adequately for their children was a core factor in deciding to offend (discussed in more detail in the Economic Pressures section below).

On the other hand, issues surrounding custody and access to children were common, and a hugely emotional influence upon several. Conflicts over regaining custody, or making the decision to relinquish custody were frequently cited as triggers to downward spirals. Julie, a Māori woman in her 30s, had recently left an abusive relationship but had also given custody of her children to their father in order to achieve space to 'sort herself out'. However, conflicting feelings about these decisions were traumatic, and led quickly to re- offending. As she explained:

I had the kids but then I sent them away until I sorted myself out but when I sent them away I just started hard-out indulging in drugs to push the feelings I had with their Dad and everything that happened.

Children's problematic behaviour also caused stress, with the period immediately following release from prison being the most difficult. Some of the women spoke of their own children getting involved in criminal offending. Feelings of guilt for having been 'a bad example' were for several women a factor in once more 'spiralling down' into crime.

Finally, many women spoke of their strong desire to look after partners, parents and children, that meeting the needs of these others was crucial for them having self-respect. Guilt from failing to be the good wife or daughter, and especially mother of their children, was for many a huge frustration.

Addictions and Substance Abuse

The majority of the women in this study had substance abuse problems; a few also acknowledged gambling as an addiction. For a number of women, alcohol and drug use continued as before when they returned to the same networks of family, friends and partners. As noted extensively above, substance abuse was also initiated and renewed as a means of coping with life stressors, including deaths of family members, family conflict, loss of custody of children, abusive relationships, and feelings of guilt, shame and isolation. Julie, who had recently left an abusive relationship and lost custody of her children, explained: 'it just kills the emotion, you don't have to feel all that stuff … some of that stuff's real depressing'.

The relationship between addictions and offending was however complex: in some cases the direct link from addiction to committing an offence was obvious, and for these individuals renewed addiction was perceived to be a main risk factor for future re- offending. For those whose substance abuse was more directly implicated, the resulting offending tended to be shoplifting, frauds, burglary and drug manufacture and supply. Some described selling and stealing purely to support drug habits, and the drug habits of family and partners. Kim had a long history of meth use and stated, 'I wasn't doing it [drug manufacture and supply] for the money, I was doing so I wouldn't be sick everyday'. She was also funding her father's drug habit. Some had also committed crimes while under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol, including drunk driving, violent crime, and property damage. For others, substance abuse was seen to play a more indirect role, simply being one of a number of contributors to the general instability that preceded offending.

Economic Pressures

Women frequently pointed to financial pressures in the immediate post-prison period and later on as their main offence trigger. These women identified common stressors which they felt unable to deal with, and so returned to theft and drugs to make money. These included:

-

the financial grant to released prisoners ('Steps to Freedom') was inadequate for the immediate expenses faced for themselves and their children;

-

delays in getting a benefit

-

costs related to housing, including mortgage payments, rent and utilities

-

unstable housing; and

-

inability to find work.

For some women, returning to crime was immediate, rationalised to themselves as a 'temporary measure' until they got back on their feet. However, once offending resumed it then tended to continue and escalate. Kathleen served a prison sentence for drug

supply. She described financial pressures with housing and children after getting out of prison, and being unable to find work. After resuming contacts with former associates, and sliding into the same behaviour patterns, she recalls thinking 'go back, do a few deals, get some money, and then I'll stop' - instead her offending simply continued until she was re-arrested.

For some of the women, extended offence-free periods were interrupted by a sudden financial shock - such sustaining an injury that meant they had to quit their current job, or suddenly resuming custody of children - which precipitated a return to crime. On the other hand, the financial 'trigger' precipitating renewed offending was sometimes a simple case of 'greed' (as some openly termed it). An opportunity for easy money would present itself (or be presented by associates) and the women would act on it. Mahi, a Māori woman in her 40 with a history of fraud offending, had recently gained a business qualification. After becoming aware of a situation that she saw as 'ripe' for fraud, she decided to act. She spent some of the money on her children, but suggested that this was not the sole motivation: she was 'not really needing it, just wanting it'.

Employment

Women frequently mentioned lack of employment in the period after release from prison as a problem. For some, job opportunities evaporated when their criminal record became apparent. Raven, a Māori woman in her 20s, described this issue: 'my criminal history is the one thing that holds me back. I wouldn't just leave here and try to do nothing, I've tried'. Frustrations around not being able to find work, and feeling doubly disadvantaged by having a criminal history, were mentioned as contributing factors to re-offending.

Others of the women had long histories of unemployment or had never had a legitimate job. Tui, a young mother, admitted that 'pretty much all I've done my whole life is shoplifting'. Low confidence acted as a barrier to some women finding employment. Mahi, mentioned above in relation to fraud offending, described how at that time she did not have the confidence to seek employment due to a fear: 'I just got my diploma (but) I couldn't apply for jobs because I was so scared of rejection'. She had not had a job since having her first child at 16.

Others were turned off by the idea of a stable employment. Marama commented said none of the jobs she had ever had 'stimulated the juices to stay at it … breaking the law, almost getting caught, that's the adrenalin'.

Support networks and neighbourhoods

Few of the women had pro-social friends, instead associating mainly with gangs or others involved in drug and alcohol use and crime. While not blaming their associates for their continued offending, women returning to old networks were clearly at greater risk of re- offending. These social networks were difficult to avoid or escape from for a variety of reasons. Those involved with gangs described them as 'like family'. Some of those being released from prison and returning to the same area found that old associates easily tracked them down. Trying to make new friendships with pro-social others was experienced as stressful and difficult.

Many of the women described knowing that they needed practical and emotional support, and that having this support would lessen the likelihood of re-offending. They described a range of barriers to seeking out and accessing support networks. This included lack of trust in public agencies or institutions, pride, shyness, feelings of worthlessness and low self-esteem. Casey explained how this played out, 'probably because I'm too proud I didn't want to seek help I wanted it to come to me, like I'm like oh I don't need help - but really I did.' Even when women had viable support networks, shame and guilt associated with not coping acted as a barrier to asking for help. Brenda, a European woman in her 40s described how she had lost confidence to seek help:

I got to the point where I was feeling so worthless I didn't actually want to go to any of the friends who would have helped me … I guess for me I just lost the confidence to keep going back and asking because, when you've been knocked back a few times, you just start to give up, it's a lot easier to just go and have a drink.

Even when services were known to be available, some women's internalised beliefs that they should be self-reliant and 'solider on' meant that they did not seek these out.

Some women were entirely unaware of what services were available to them. Those who sought material supports (such as benefits or food grants) or services for addictions, mental health and other offending-related issues spoke of not being able to access services. Referrals were not made, or went astray, waiting times were interminable, services had been discontinued or had relocated elsewhere, or the women did not meet eligibility requirements.

For example, Jane tried to get help when she feared that she was about to commit fraud, but didn't know who to go to. She tried Gamblers Anonymous but was told they could not help her. For some women, frustration, distress and feelings of neglect these difficulties inspired triggered renewed offending. Sophie's experiences illustrated this. Amidst the frustration stemming from not being able to access the support she wanted, she reverted to fraud:

I have learnt from all my courses out there that there is support all you have to do is ask and yet when I did ask it was just another barrier, another hurdle. Sometimes those hurdles are just, you can't climb them sometimes.

Summary

A range of things 'went wrong' for these women which became precipitators of renewed offending. Predictable or unforeseen financial hurdles arose. Relationships with family deteriorated, they lost custody of children or became trapped in abusive relationships. Old addictions resumed or new ones developed. While many of the events faced were clearly traumatic, the stresses and pains these women faced are probably not dissimilar to those faced by other women who nevertheless do not re-offend. The ways women described how they saw themselves, their past and current relationships, and the way they responded to challenges may help to answer the question of why some fail while other 'survive'.

The backdrop to their offending was almost always histories of limited education, economic marginalisation, violence and trauma, all of which continued to affect how they saw themselves, the types of relationships they entered, and the future prospects they envisaged. Women often felt trapped in cycles of offending which meant their sense of self was very tied to being an offender and crime had become a way they met emotional needs. Many women felt they did not have the capacity to create a different life and remain resilient when confronted with emotional setbacks, especially when they had little outside support. When faced with troubles, decisions were made to revert to scripts that they knew, while others felt they could not control their emotions, and crime was the end result of a general 'unravelling'.

Tendencies to prioritise relationships was a frequent point of tension as women attempted to provide for the financial and emotional needs of others, often with little reciprocation for their own needs. In trying to understand the offending that occurred, it was not always that the women did not think that they could live crime-free, but that they couldn't live crime-free and maintain the current relationships. This finding may suggest a need to focus programmes on assisting women to develop more productive ways to manage relationships, to survive stresses, and to seek support when needed.

Women’s perceptions of their rehabilitation

Female offenders have access to a range of rehabilitation programmes and services while serving sentences in the community and in prison. The rehabilitation experienced by the women interviewed fell into three main categories: motivational, offence-focused and drug and alcohol treatment. The extent to which the women involved in the research had accessed these programmes and services in the community and in prison, over the previous six years, are summarised Appendix A.

This section of the report discusses women’s perceptions of the rehabilitation interventions they received, including what types of programmes and approaches to programming they found useful, and what they perceived as gaps. It should not be read as an evaluation of individual programmes, but rather as a discussion of what the women perceived as helpful – or not helpful – in trying to desist from crime. This section is structured around five key elements of the rehabilitation experience that emerged as important to these women:

- The pathway to identifying the right kinds of rehabilitation for the individual: issues around being consulted, being informed about options, how decisions were made, and how progress was acknowledged.

- The extent to which they were helped to understand the underlying drivers of their offending, how their past experiences may have shaped their current offending, and how these dynamics might influence their future choices.

- Issues around self-identity, self-esteem and emotional resilience, especially in relation to relationships - recognising and responding to “bad” relationships, and building positive relationships with partners, family and children.

- Accessing practical and emotional support in the community.

- Tailoring interventions individually to meet the range of needs.

The current research did not focus on procedural matters relating to how needs were identified, referrals made, or the roles of Case Managers, Corrections Officers or programme personnel. It centres on the perceptions and reactions of these women who went through the process of engaging with what was available to them as offenders.

Accessing treatment should be a motivating process

The ways that Department staff interacted and communicated with the women about their needs, and the processes used in identifying needs, was revealed as having had a significant impact on how the women felt about rehabilitation and how they responded.

Respectful Relationships with Staff

The women valued having good relationships with Case Managers and Probation Officers. A Case Manager or Probation Officer was regarded positively when they consulted a woman on what she thought her needs were, gave her information about the options available, and conveyed a sense that she could exercise choice. Some women however felt that they were not treated like individuals, were not consulted over what their needs might be, and did not have their requests listened to. Several described making requests for programmes or services which they believed would be valuable, such as counselling, anger management, violence prevention programmes, or dishonesty-related programmes, but being informed that they did not meet programme entry requirements, programmes no longer existed, or waiting lists were too long. A common concern centred on a lack of information about what programmes and services were available. Those on shorter sentences were most likely to have been disadvantaged by this issue in relation to accessing appropriate programmes. Some women reported that long waiting times to enter a programme were demoralising and demotivating.

Delays in seeing Case Managers, starting programmes, or getting the programme or services that they wanted was to an extent expected. However, the core issue appeared to be how information was communicated, and how expectations were managed. Making it clear what is available, what women can expect with regards to timeframes, and the reasons for this, is likely to lead to better engagement and maintenance of motivation.

Motivating environments

Women in the community often needed to fit employment and childcare responsibilities around the programmes they were required to attend. This was often problematic. Also noted were occasions when women were the sole female on a community programme, which for some was an uncomfortable experience. There were differing opinions about group versus individual programmes. Many women found talking about their past experiences and offending histories difficult. Some women liked doing this in a group environment, and found the sharing of similar experiences beneficial. However, those who were talking about personal issues perhaps for the first time sometimes found group environments confronting and preferred, at least initially, to have one-on-one support. Women appreciated having their preferences listened to with respect to such issues.

Another factor that emerged was the importance of progress being recognised and acknowledged by staff. Some spoke of Corrections Officers who showed them little respect and who seemed cynical about their sincerity in trying to make changes. Comments in a similar vein were made about Probation Officers, especially by women who had transitioned from prison to the community after completing programmes. Marama explained the downsides of a Probation Officer who failed to recognise the progress she had made:

Because if you’ve always been judged your whole life then all of a sudden you’ve got this person judging you from a piece of paper, and they don’t know the journey you’ve come on to get to a certain point, then they’re just pushing you right back.

Similar comments were made about counsellors and facilitators. They were considered to be most effective when they were understanding and non-judgemental. It was also perceived as advantageous if the professionals had had similar experiences of addictions or disadvantage in life, and had overcome these: some women felt it made the person better able to understand their situations, and serve as a role model.

Making sense of the past

Interviews revealed a number of women’s beliefs that their rehabilitation was at least in part dependent on gaining a better understanding of their past, and how experiences of family dysfunction and abuse had affected them. Such insights were perceived as forming the first step to contemplating a different lifestyle. A number of women who had done intensive offence-focused programmes spoke of moments of insight to how behaviours relating to their offending had been learned. This included, for example, that witnessing and experiencing abuse had diminished their trust in others and made it difficult to ask for help, or how being a ‘people pleaser’ made them more likely to get into (and stay in) abusive relationships. Similarly, AoD treatment which not only focused on addiction issues but allowed exploration of the deeper, historical drivers of these addictions was perceived as useful. Unfortunately this was often not the case. Many programmes were experienced as too brief or superficial to allow such examination. As one woman commented, ‘when you’ve sat with these issues for all these years it’s going to take you more than eight weeks’.

Several women serving sentences for dishonesty and burglary were frustrated that the programmes they had completed did not include any exploration of what many experienced as compulsive behaviour. Unable to understand their behaviour, they felt unable to change it. Raven, who had a history of dishonesty and burglary, described her frustration, stating that, ‘I really needed their [psychologist’s] help, I wanna know why, I need it because I want to know why I keep re-offending’. Evident within this narrative, and amongst others, was the belief that breaking the cycle of offending first required understanding what drove it.

A desire to understand the drivers of offending did not appear to represent the desire to absolve themselves of responsibility. In fact many expressing such a desire were able to describe how certain ideas and beliefs held at the time justified and legitimised their offending. “Seeing through” these distortions was helpful in enabling them to desist. Offence-focused programmes in particular had helped a number of women understand that they had been normalising and minimising their offending behaviour, and not seeing it as crime. Alexis’s experiences of the Short Motivational Programme were illustrative of this:

The programme [SMP] made me think if I keep going round in the circle of blaming, I’m not going to get anywhere. It sort of gave me a bit of insight into how to take responsibility for myself and not blaming everyone else.

However, this issue of explanation versus responsibility was fraught for some. Understanding past relationship experiences, the impacts they had on behaviour and how they continued to act as a trigger, was necessary for some women to recognise how to change their behaviour and move forward. Alexis’s experiences were once again illustrative of this. Her offending appeared related to the trauma of an abusive relationship, and preceding family conflict. She described how important ACC counselling had been in getting better insight into her behaviour and how her experiences of witnessing abuse and experiencing it had shaped her behaviours and current relationships, and the need to have better relationships:

I think for me what’s important is maybe maintaining that ACC stuff and dealing with all that icky sort of shit that happened between Dad and Mum and trying to separate, and just try to have an adult relationship with them.

‘The will and the way’: Identity and Resilience

Research on desistance has shown that offenders need both ‘the will and the way’ to desist. That is, the desire to desist from crime must be accompanied by self-belief that it is achievable, and skills both to forge a new lifestyle and deal with personal setbacks. In this research, some women spoke of needing rehabilitative programmes that were future- focused and gave them ‘hope’.

‘The will’: Building confidence to develop a pro-social identity

Women frequently perceived themselves to have been devoid of hope or belief in their ability to change: the criminally-oriented lifestyle seemed was “just the ways things were”. To develop a desire for something different, many reported that rehabilitation programmes needed to build their self-esteem. To them, this term appeared to mean helping to build confidence that they could move away from a criminal lifestyle, could be a different person, and could be happy in this new way of being. Tracey described how programmes should be about ‘empowering ourselves and giving us the strength to walk another path’.

Rehabilitation that encouraged women to think positively about themselves, to recognise their strengths, and see themselves in a pro-social way, was therefore valued. Tikanga programmes appear to have helped some women: Casey described how the Tikanga programme she took helped her to develop “a new identity”, distinct from the person she was within the drug-centred world she had previously felt lost within. Sophie described how the focus on self-esteem in a Salvation Army “positive life skills” programme helped her to recognise her own strengths as a person and a mother.

Some women described having to speak up for themselves within group programme situations as quite helpful in developing self-confidence. Creative activities were mentioned in a similar vein: creative writing, book clubs, quilting and music allowed them to explore and recognise strengths they already had.

Developing boundaries and putting the ‘pro-social self’ first

As noted, a recurring theme in the research was the tendency to be unassertive with respect to the women’s own needs, instead being ‘people pleasers’ who acquiesced to expectations, needs and desires of others. Programmes that explored this tension were seen as productive: understanding the impact of expectations (to be a good partner, daughter, etc), and how to balance this with taking care of themselves and asking for help, were perceived as useful.

The importance of understanding, and developing personal boundaries also emerged. Jackie quickly returned to drug dealing after release, having moved back in with her mother who was alcoholic. Pressure to contribute to the mortgage contributed to her deciding once more to involve herself in the drug trade. Since returning to prison, however, a new programme:

… taught me about saying ‘no’, about putting myself first - instead of being released like I was last time and thinking about everybody else, about losing the house, and the kids, about how to make money. That’s not what it’s about. If it’s offending, that’s going to affect me then I have to stand up and say ‘well, hey, if we’re going to lose the house we need to work together, it’s not up to me to go and do illegal stuff’ … I can’t do that anymore, I’m moving past this. And I need to be able to stand up, and say that.