Public protection orders - Managing the most dangerous offenders under a civil regime

Michael Herder

Senior Policy Adviser, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Michael joined the Department of Corrections Strategic Policy Team in 2014. His areas of interest include strategies to reduce re-offending by high-risk offenders, and the management of offender identities in the criminal justice system. As well as working for Corrections, he tutors Public Policy at Victoria University, School of Government and is studying professional economics part-time.

Introduction

New Zealand has experienced success in recent years with overall crime rates dropping to a 30 year low in 2013/14. While this is a significant achievement for the justice and social sector, there are still areas where public safety can be improved. One of the most important and challenging areas is the ability to protect New Zealanders from a small group of individuals who pose the greatest risk to public safety. While this small and unique subgroup of offenders has a limited impact on the overall landscape of crime in New Zealand, and the approximate 350,000 offences recorded every year, the potential harm these offenders could cause would have a significant and long-lasting impact. There is a need to continue to protect the public from near-certain serious harm where an offender still poses an undue risk on release from prison. The introduction of public protection orders (PPOs) in late 2014 made inroads to address this area – providing Corrections with a unique tool to manage serious sexual and violent offenders in a separate civil facility on prison grounds after completing a finite prison sentence.

Problem definition

Despite serving finite prison terms and having the opportunity to participate in rehabilitative programmes, a small number of dangerous offenders will be highly likely to re-offend once they have been released from custody. Existing measures such as extended supervision orders and preventive detention enable some offenders to be closely monitored and recalled to prison if necessary to respond to their level of risk. However, these arrangements are not always adequate to protect the public from the most dangerous offenders with bespoke management needs. Specifically, a further measure was needed to protect the public that could be imposed towards the end of a finite sentence if preventive detention was not considered to be appropriate at the time of sentencing. The near-certain risk of imminent serious harm served as a compelling rationale for a new measure to detain the most dangerous individuals in a secure civil facility until they no longer pose a serious threat to public safety.

Comparable jurisdictions, such as the United States, Canada, and Australia, also recognise that there will inevitably be a small number of dangerous offenders who are highly likely to re-offend after serving a finite sentence. The most common approach used internationally to protect the public from these offenders is the use of indeterminate sentences (equivalent to that of New Zealand’s preventive detention), or extensions to finite sentences, which are imposed at the time of sentencing. These measures are used even by the more progressive jurisdictions. For example, Norway has a maximum sentence of 21 years for most crimes, which can be extended for five years at a time if deemed warranted due to the continued threat to society.

In New Zealand, preventive detention is imposed by the High Court at sentencing if satisfied that the offender is likely to commit another serious sexual or violent offence if released at the end of a finite sentence. The United Nations Human Rights Council and European Court of Human Rights have determined that this does not breach international human rights obligations. Establishing this at the time of sentencing means that further measures are not imposed retrospectively, and prevents human rights issues of double jeopardy. However, it is not always possible to determine an offender’s future level of risk at the time of sentencing, considering the potential positive behavioural progress an offender may make during their time in prison. Extending the use of indeterminate sentences may also not be a desirable or proportionate response to offending as part of overall sentencing practice.

If an offender does not receive an indeterminate sentence, the alternative option is to impose an order at the end of a finite sentence if they continue to pose a high risk of serious re-offending. Because the order is imposed at the end of the sentence, there are wider human rights aspects to be considered in order to be consistent with New Zealand’s Bill of Rights Act and international obligations. In particular, there are issues relating to double jeopardy and the unfairness of imposing measures retrospectively. This saw the development of PPOs as a civil order, rather than a criminal punishment, to ensure that individual rights are upheld as far as possible while reducing the risk of serious violent and sexual harm to the public. The introduction of PPOs is a unique move for New Zealand, with limited comparable models internationally.

Eligibility for PPOs

The Department of Corrections can only apply for a PPO for individuals who have previously been convicted of a serious sexual or violent offence, and are still serving a finite sentence. The assessment process to consider whether an individual meets the high threshold to be detained in the residence is robust. In assessing an individual’s level of risk, at least two reports must be undertaken by separate psychologists to determine whether an individual meets the threshold. An advisory panel (consisting of Corrections, Police, and Child, Youth and Family staff) then considers this risk assessment and whether to recommend for the Chief Executive of Corrections to make an application to the Court for an order in the interests of public safety.

A High Court judge will make the ultimate decision whether to impose a PPO if he/she is satisfied that the individual presents a high risk of imminent and serious sexual or violent offending if released from prison or, in any other case, left unsupervised. This test is higher than the test for preventive detention. In particular, the individual must exhibit the following characteristics to a high level:

- an intense drive or urge to enact the particular form of offending

- very poor self-regulatory capacity, evidenced by general impulsiveness, high emotional reactivity,

and inability to cope with or manage stress and difficulties - absence of understanding and concern for

the impacts of their offending on actual or potential victims - poor interpersonal relationships and/or social isolation.

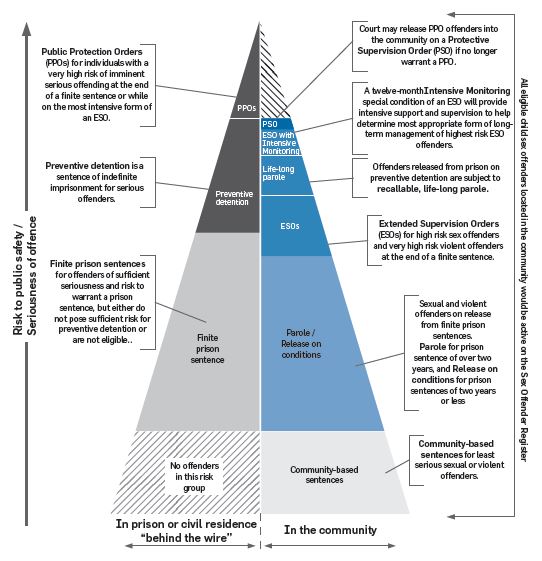

Due to the high risk threshold examined through extensive psychological assessments, only a very small number of people are likely to be subject to PPOs, estimated at between 5 – 12 every 10 years. There is a high legal test for an order to be imposed, requiring that a person must pose a very high risk of imminent and serious sexual or violent offending after serving a finite sentence. Without this high threshold, continuing to detain someone after serving a finite sentence would amount to arbitrary detention. All offenders subject to a PPO will have either had, or been offered, comprehensive treatment during their time in prison and demonstrated little or no progress through rehabilitative programmes. It is expected that the majority will be child sex offenders, with a small number of adult sex offenders and other violent offenders who may also meet the criteria. Offenders who do not pose an imminent risk of re-offending and do not meet the high threshold for a PPO may be managed in the community on an extended supervision order. A breakdown of where PPOs fit in the hierarchy of sentences and orders available to manage offenders is illustrated in the figure opposite:

Managing the most dangerous offenders under a civil regime

A defining feature that makes PPOs particularly unique is that they are civil detention orders, rather than criminal punishments where an individual is detained in a custodial environment. Civil detention orders are already used as part of other regimes to protect the community where there is an undue risk of harm that needs to be managed. These include detaining people who have mental health or intellectual disability issues that make them a danger to others or themselves, or in rare cases for individuals with a highly contagious disease. The particular challenge faced in developing the PPO regime was the need to create a civil environment that protected the public from the most dangerous offenders who pose an imminent risk of serious re-offending in a way that adequately upholds individual rights and freedoms.

The core purpose of PPOs is to protect the community from almost certain future harm posed by the most dangerous offenders, rather than to impose a further punishment after serving a finite sentence. To legitimately achieve this and to avoid a form of double jeopardy, individuals subject to PPOs will be detained in a civil facility rather than in prison and be entitled to the same rights as ordinary citizens and provided with as much autonomy as possible without endangering others, themselves, or the orderly functioning of the residence. Any limits on an individual’s rights will be justified by the danger posed to the public if they were not able to be managed securely.

To achieve a civil environment, the PPO residence will be separate from the existing prison and have its own secure perimeter fence. Residents will live in individual units, which will resemble a basic home rather than an institution or prison cell. There will also be communal areas, such as kitchen and laundry facilities, visiting and interview areas, and indoor and outdoor recreational areas where individuals will have freedom to choose how to structure their daily activities.

To ensure that the rights of residents are upheld in accordance with a civil regime, there are important safeguards to ensure that they are only detained for as long as their level of risk to public safety warrants it, and that their rights are upheld during their detainment. Each individual case is regularly reviewed to consider whether the continuation of a PPO is warranted relative to the individual’s level of risk to public safety. An independent review panel (similar to the New Zealand Parole Board) is required to conduct annual reviews of every PPO, and can direct the High Court to review the continued justification of the order. The High Court must also conduct its own review of every PPO once every five years. Individuals who are subject to a PPO also have the right to apply for a court review of their order at any time.

If the Court considers that a resident no longer meets the high threshold for a PPO, they will be released and placed under a protective supervision order involving community supervision (similar in practice to an extended supervision order with intensive monitoring). Protective supervision orders will also be reviewed regularly or on application to the High Court, with the possibility of this order being cancelled after five years.

In addition to regular reviews, independent inspectors will oversee the operation of the PPO residence to ensure that residents’ rights are upheld and that their accommodation and management reflects their status as detainees under a civil detention environment. Inspectors are required to make regular visits to inspect the facilities, conduct investigations into alleged breaches of rights and deal with complaints. Certain office holders also have the right to visit and examine the residence and residents, including the Ombudsman and the Privacy Commissioner.

Conclusion

The civil regime of PPOs has been developed to appropriately balance the right of New Zealanders to be free from almost certain serious harm, with the rights of offenders who have completed a finite sentence. This has been a unique approach for New Zealand to address this issue through measures other than increasing the use of indeterminate sentencing, and overall provides a considered regime with greater rights and freedoms for offenders in comparison to spending increased time in a custodial environment.