Addressing the imbalance: Enhancing women's opportunities to build offence free lives through gender responsivity

Hannah McGlue

Principal Adviser Women, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Hannah has recently been permanently appointed as the Principal Adviser Women after being seconded to the role for 12 months. Prior to this appointment she worked on developing a strategy for women while in the Chief Custodial Officer’s Team as the Principal Adviser National Systems. Hannah joined Corrections as a Corrections Officer at Auckland Region Women’s Corrections Facility.

This was after completing a law degree and post-graduate study to become a barrister in England. Since 2013 she has worked in strategic and operational policy roles at National Office.

“Some of the most neglected, misunderstood and unseen women in our society are those in our jails, prisons and community correctional facilities. While women's rate of incarceration has increased dramatically … prisons have not kept pace with the growth of the number of women in prison; nor has the criminal justice system been redesigned to meet women's needs, which are often quite different from the needs of men.” (Covington, 1998).

Since 2015 the Department of Corrections (Corrections) has been developing and beginning to implement a strategy and programme of work to improve outcomes for women on sentence in New Zealand. In that time the author has fielded a wide range of questions which all boil down to: “why do women need their own strategy, what about treating men and women ‘equally’?” In the context of the world we live in, this question is not surprising. This article answers that question and outlines how Corrections is seeking to change its approach to the women who come through our doors by addressing the imbalance in opportunities available to women, and the relevance to the reality of their lives.

Women and the criminal justice system in New Zealand

Women make up the minority of people managed by corrections services across the world. In the majority of countries, women account for between four and 14 percent of prison populations, and around 20 percent of people serving community based sentences. In New Zealand, women currently account for 7.5% of the prison and women who offend, which support the need for a gender-specific approach. The first is that women’s offending needs and pathways to crime are often different from men’s. The second is that women’s responses to treatment and management are different.

On the whole, women commit less serious crimes than men and re-offend at lower rates. These are the main reasons why criminal justice systems’ policies, process, practices, services and interventions are usually designed with men in mind.

Over recent decades the world has seen significant increases in the rates of women’s imprisonment and changes to the offences and characteristics of women in the criminal justice system.

New Zealand has not fared any differently and, in particular, over the last decade we have experienced increases in:

- the total number of women managed by Corrections

- the number of women starting community sentences

- the volume of women sent to prison for serious offences, particularly drug related offending (methamphetamine) and violent offending

- the proportion of women being sentenced to imprisonment for breach offences

- recidivism among women

- the proportion of women who are categorised as medium and high risk

- the numbers of women remanded in custody at any one time

- Mäori women’s overrepresentation in prison.

Women tend to be in prison for less serious offences than men, with violent offenders making up a smaller proportion of women’s prison starts. Across prison and the community, the most common offence type for women is dishonesty (approximately 30%). This is followed in the community with traffic offences (approximately 29%) and in prison starts by violence (approximately 18%) and breach offences (approximately 16%).

Gender responsivity in the criminal justice system

These trends, alongside greater academic interest about what works to enhance women’s opportunities to live offence-free lives, have led to the concept of gender responsivity in the criminal justice system. Gender responsive services for women are those which are designed to meet women’s needs, and are not confined to criminal justice.

Gender responsivity has been slowly adopted in various forms across corrections systems. Canada, Scotland, Australia, England and Wales and parts of the United States all have strategies, standards, policies and practices predicated on becoming more responsive to women’s needs.

While the intricacies of gender responsivity in corrections settings vary, and jurisdictions are at different stages of implementation, current best practice dictates that to be gender responsive:

- programmes and services, including reintegrative services, are designed to meet women’s unique needs (offence related, socioeconomic, mental health, alcohol and drug, trauma)

- women are provided with a safe, respectful and dignified environment to address their risks and needs (trauma-informed care and practice)

- relational approaches to women’s management are taken, and healthy connections and relationships encouraged and fostered (Bloom, Owen and Covington, 2003).

To put these principles into practice, other jurisdictions have implemented a range of initiatives including building small regional units focused on treatment rather than building a large women’s prison (Scotland), building culturally responsive healing centres in place of prisons (Canada), focusing on greater use of non- custodial sentences for women (England and Wales), innovative expansion of policies to enhance women’s relationships with children, partners and family (Australia, England and Wales), introduction of healthy relationships programmes (all) and introduction of trauma-informed practice (USA, Scotland, England and Wales).

Why women need a distinct approach

There is strong international and domestic evidence that a specific approach for women is required in New Zealand, and in some areas we already take one. There are two key differences between men who offend and women who offend, which support the need for a gender-specific approach. The first is that women’s offending needs and pathways to crime are often different from men’s. The second is that women’s responses to treatment and management are different.

This means that what we work on and how we work with women needs to be informed by evidence of what works for women.

Women’s needs – what we work on

There are a number of factors which influence, or cause, the offending of men and women regardless of gender. In line with this, Andrews and Bonta’s

evidence-based principles of risk, need and responsivity are the basis for Corrections’ programmes designed to reduce women’s risk of re-offending. The focus of this treatment is on the personal characteristics of women that can cause their offending behaviour. These include antisocial attitudes, antisocial associates, history of antisocial behaviour and antisocial personality pattern, personality as well as substance use, problematic home/family circumstances, school/work circumstances and leisure/recreation circumstances (Andrews and Bonta, 2017).

Having said that, research focusing specifically on women’s pathways into crime has shown that women’s fundamentally gendered experiences are often factors in their pathways to offending. These “gender specific” factors include:

- Lifelong trauma and abuse (Bevan, 2017; Salisbury and Van Voorhis, 2009)

- Mental health issues (Indig, Gear and Wilhelm, 2016), with self medicating behaviour and coping mechanisms

- Unhealthy personal relationships (Bloom, Owen and Covington, 2003)

- Parenting difficulty and stress (Covington, 2007)

- Economic marginalisation, including difficulty providing financially for dependent children and other family (Wright, Van Voorhis, Salisbury and Bauman, 2012).

In particular, research consistently shows that women are likely to present with multiple needs (greater than their male comparators), and those needs are likely to be intertwined (Bevan and Wehipeihana, 2015). For example, traumatic experiences such as sexual abuse leading to post-traumatic stress disorder, leading in turn to substance misuse as a coping strategy.

Research conducted by Corrections on women’s experiences of re-offending and rehabilitation (Bevan and Wehipeihana, 2015) mirrored the international research about the needs and re-offending triggers of women. Four key trigger areas were identified by women as things that had “gone wrong” and led them back to offending, sometimes after long periods of desistance. These triggers were relationships going wrong; reliance on drugs, alcohol and gambling; economic pressures; and lack of good support networks and services (Gobeil, Blanchette and Stewart, 2016).

Additionally, it was typically the underlying beliefs they held about themselves, their roles in society and their perceived levels of agency that influenced how they responded to the challenges they faced. Within the context of relationship difficulties, economic pressures, substance abuse issues and a lack of support, many women felt they did not have the capacity to create a different life and remain resilient when confronted with instability.

This research also asked women about their experiences of the rehabilitation opportunities provided by Corrections. While the women in the research highly valued the rehabilitation that they had received, they also frequently felt that their rehabilitative needs were not adequately met. In particular, their needs relating to the experiences mentioned above (relationship issues, trauma, mental health and substance use) and the way they interact with each other were frequently cited as having not been identified, addressed or addressed in sufficient depth for them to make the changes in their lives they needed to stop offending.

In summary, research has highlighted the importance of paying attention to gender. This includes research which has compared outcomes for women who have received gender-neutral interventions, with women who have received gender-responsive interventions, which supports the idea that women are more likely to respond well to gender-informed approaches (Gobeil, Blanchette and Stewart, 2016). This means we must understand the way that gender shapes women’s early experiences, opportunities, expectations about their roles in society and the way they try to manage the range of tensions in their lives, and support them to overcome these when they are barriers to reducing their risks of re-offending.

Women’s responses to treatment and management – how we work

Working with women in criminal justice settings is different to working with men. People who have worked in both women’s and men’s prisons, and with different genders in the community, frequently articulate the differences and challenges from each group. Women’s different life circumstances, needs and ways of behaving and interacting with other people are all relevant and need to be accounted for to successfully manage them in a gender responsive way.

For example, research focused on behaviour in prison has shown that women often have different communication styles and interpersonal skills than men: they are more likely to communicate openly with staff, including being more open about their needs and emotions and more likely to form close relationships with others on sentence (Wright, Van Voorhis, Salisbury and Bauman, 2012). New Zealand research into women’s case management in prison has recently confirmed this in our context (Bevan, 2017, draft). This means that staff will be more effective with women when they take a collaborative approach which allows time for a trusting and empathetic working relationship to be built. Support for women to navigate the stresses of their relationships is also a required skill when working with women.

Mental health issues, substance dependence and trauma often play a significant role in the lives of women who offend, which directly impacts how they should be managed. While the prevalence of mental health and problematic substance use issues is high across the male and female offending population, analysis indicates that it is starker among women (Indig, Gear and Wilhelm, 2016):

- 75% of women in prison have diagnosed mental health problems (61% male prisoners)

- 62% of women in prison have co-morbid mental health and substance disorders across their lifetime (41% male prisoners).

The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder is particularly high among women prisoners. The source of trauma is varied; however, a high proportion of it is likely to be through violent and sexual victimisation as a child or adult. Recent analysis has shown that 75% of women have experienced family or sexual violence in their lifetime (Bevan, 2017). Historical trauma, “the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding…spanning generations, which emanates from a massive group trauma” (Brave Hears, MYH, 2005) is also a relevant consideration, particularly for Mäori women in prison.

While traumatic experiences do not always translate into long term difficulties, some experiences have pervasive impacts. It can be particularly difficult for those individuals to cope in a prison environment or while on sentence in the community. Women’s mental health issues and on-going symptoms of trauma can be difficult for staff to respond to and manage, especially when they are not trained to work in a trauma-informed way with women.

The relational theory of women’s psychological development is also important here. It maintains that fostering relationships and strong connections with others is a primary motivation for women that directly informs perceptions of self-identity and worth. Relational management is about the way we engage with women, and the strategies we implement to best engage women in their pathway to desistance. In practical terms, relational management sees staff proactively forming empathetic relationships with the women they work with and encouraging the growth of healthy relationships with children, whānau, partners, family, other women on sentence, community services and corrections staff.

Applying gender responsivity in a New Zealand context: Wāhine – e rere ana ki te pae hou, women rising above a new horizon

In response to the changing shape of the women’s offending population in New Zealand, including a 40% increase in the women’s prison population in two years, we have incorporated what we know about women who offend in a new Women’s Strategy (the strategy). The aim of the strategy is to enhance women’s opportunities to create offence free lives for themselves through:

- Providing women with access to interventions and services which meet their unique risks and needs

- Managing women in ways which are trauma- informed and empowering

- Managing women in ways which recognise the importance of relationships in their lives

For the avoidance of doubt, the Women’s Strategy is not about neglecting men. It is not about ignoring men’s needs. It is not about making prison or community sentences easier for women than for men. It is, in fact, not about men at all. The strategy is about making sure that we are giving women the best chances we can to change their lives.

Providing women with access to interventions and services which meet their unique risks and needs

This priority is about addressing the imbalance. As the minority population, services provided to women in the criminal justice system have often been retrofitted from those designed for men, or not provided in equitable quantity or quality. Through this priority we will make sure that women on sentence have sufficient access to rehabilitation treatment, interventions and services to enhance their ability to build offence free lives in the community.

To achieve this priority, we will increase provision of individualised and timely gender and culturally responsive rehabilitation and intervention. This includes rehabilitation programmes, and services to address responsivity barriers such as trauma symptoms. For example, we are employing additional psychologists and programme facilitators to increase the delivery of our medium intensity programme for women, Kowhiritanga. We will provide services to identify and meet mental, physical and spiritual health needs. As well as direct health services, this includes access to health education and opportunities to improve overall wellbeing. We will provide opportunities for education, skills training, and work which broaden women’s experiences and take into account the realities of their lives. For example, training in the construction and hairdressing industries will be introduced to women’s prisons. These will lead to sustainable and meaningful employment. We will also provide reintegration services with the right mix and length of emotional and practical support for women to successfully re-join their whänau and communities.

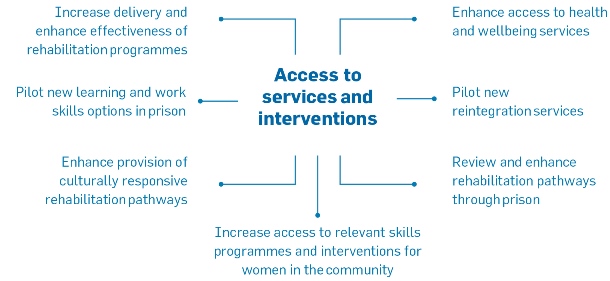

The diagram below shows some of the initiatives we are pursuing to achieve this priority:

Managing women in ways which are trauma- informed and empowering

This priority is about challenging and changing the way we manage women on a day-to-day basis. As stated above, a high proportion of women on sentence have had traumatic experiences. The impact of trauma can be “subtle, insidious, or outright destructive” (SAMSHA, 2014) and, unaddressed, can leave sufferers in a constant state of shock and self-preservation leading to behaviour such as aggression and self-harm. Corrections environments, especially prisons, can compound and worsen trauma symptoms. Moving towards practice which is trauma-informed can have positive impacts for staff and women. These benefits include a decrease in conflict between women, and between women and staff, as well as improved engagement in rehabilitation and improved mental health.

To achieve this priority we will provide training for staff so they understand the prevalence and effects of trauma, recognise the signs and symptoms of trauma and can respond to women effectively. We will integrate our knowledge into our practice, policies and procedures, and will empower women to have confidence in their abilities to build offence free lives.

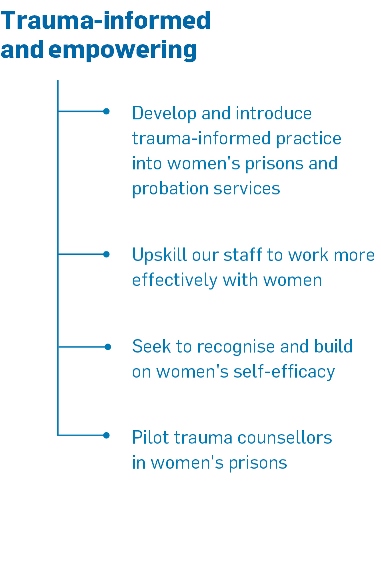

The diagram below shows some of the initiatives we are pursuing to achieve this priority:

Managing women in ways which recognise the importance of relationships in their lives

This priority is about enhancing the services we provide women to recognise the importance of relationships in their offending, and changing the way we manage women. Research tells us that women’s relationships play a unique role in their offending behaviour, and we know that relationships can be integral to the way women see and value themselves.

In a corrections context, women often value closer relationships with staff than men do, and work more effectively with staff members in that context.

Additionally, women are more likely to form close emotional relationships with other women on sentence. This means that we can be more effective working with women when we seek to enhance and foster healthy working relationships in our environments. Women’s relationships, healthy and unhealthy, with partners and children are also important here as a stable or de-railing influence. Enhancing women’s abilities to end unhealthy relationships, and foster healthy ones can be integral to their pathways to offence free lives.

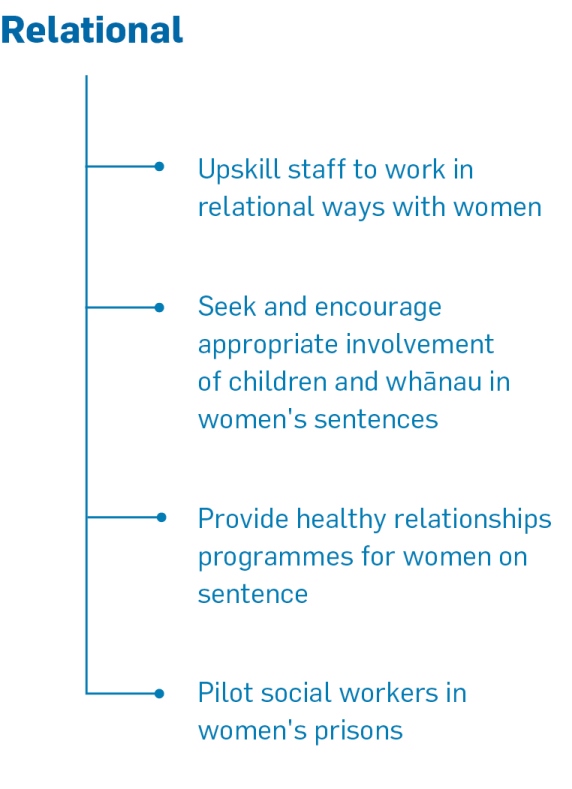

The diagram below shows some of the initiatives we are pursuing to achieve this priority:

What next for the Women’s Strategy?

In the context of increasing convictions of women for violent and drug related crime, and a significantly increased women’s prison population, it is time to try new approaches to reduce re-offending by women. Guided by international best practice, and developed in conjunction with a growing body of research about women’s offending, the Women’s Strategy has the potential to transform Corrections’ management of women on sentence.

References

Andrews, D A and Bonta, J (2017) The Psychology of Criminal Conduct, 6th Edition, Taylor and Francis

Bevan, M (2017) New Zealand Prisoners Prior Exposure to Trauma, New Zealand Department of Corrections

Bevan, M & Wehipeihana, N (2015) Women’s Experiences of Re-offending and Rehabilitation, New Zealand Department of Corrections.

Bloom, Owen and Covington (2003) Research, Practice and Guiding Principles for Women Offenders, US Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections

Brave Hears, M.Y.H. (2005) From intergenerational trauma to intergenerational healing, Keynote address at the Fifth Annual White Bison Wellbriety Conference, Denver, CO, April 22 2005

Covington, S, (1998) Women in Prison: Approaches in the Treatment of Our Most Invisible Population, Women and Therapy Journal, Haworth Press, Vol 21, No1, 2998, pp 141–155

Covington, S, (2007) The Relational Theory of Women’s Psychological Development: Implications for the Criminal Justice System, published in Female Offenders: Critical Perspectives and Effective Interventions, 2nd Edition, Ruth Zaplin, Editor

Gobeil, Blanchette, Stewart, (2016) A meta-analytic review of correctional interventions for women offenders gender neutral versus gender informed approaches, Jan 13, 2016, Sage journals

Indig, Gear and Wilhelm, Comorbid substance use disorders and mental health disorders among New Zealand prisoners, New Zealand Department of Corrections, 2016

Salisbury, Emily J., & Van Voorhis, P. (2009) “Gendered Pathways: A Quantitative Investigation of Women Probationers’ Paths to Incarceration.” Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 541–566

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) (US), (2014) Trauma Informed Care in Behavioural Health Services, Treatment Improvement Protocol Series no 57, Rockville (MD), accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191

Wright, E. M., Van Voorhis, P., Salisbury, E. J. & Bauman, A. (2012). Gender-Responsivity Lessons Learned and Policy Implications for Women in Prison: A Review. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 39(12). 1612-1632