Intervention and Support Project

Joanne Love

Mental Health Clinical Adviser, Intervention and Support Project, Department of Corrections

Rachel A. Rogers

Senior Adviser, Intervention and Support Project, Department of Corrections

Author biographies:

Joanne started at Corrections in September 2017 as Clinical Adviser for the Intervention and Support Project. Her professional background is mental health nursing, having worked in crisis teams, as a police watch house nurse, a clinical nurse specialist and in psychiatric liaison roles. Her Master of Nursing thesis was around the recognition by police officers of mental illness in detainees.

Rachel started at Corrections in August 2017 as Senior Adviser for the Intervention and Support Project. Her background is in community safety and emergency management. Rachel has worked in the Victorian Fire Service and New Zealand local government in a range of hands-on and managerial roles. Rachel has a Master of Arts in Psychology focused on behaviour modification, as well as post-graduate diplomas in community safety, and emergency management.

Introduction

Evidence suggests there are more people with mental health and addiction problems in prison than ever before. In some instances, being in custody can exacerbate and cause mental health difficulties and heighten the risk of those who are susceptible to self-harm and suicide. Funding was successfully sought to develop and pilot a new Model of Care (MoC) at three prison sites, to better identify prisoners who are vulnerable to self-harm or suicide, and to transform intervention and support for them. The MoC is a whole of prison approach that will help strengthen those individuals, allowing them to fulfil their potential and reducing self-harm and suicide.

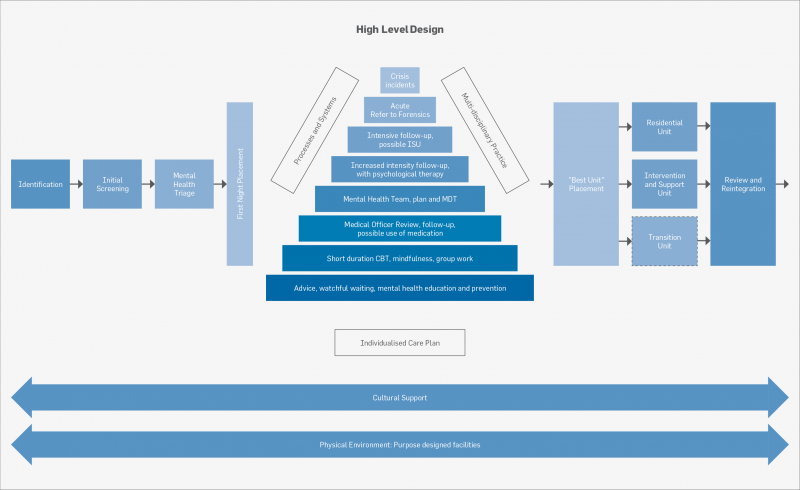

The Intervention and Support Project team (hereafter referred to as “the project team”) undertook a series of literature reviews, qualitative interviews and site visits to investigate self-harm, suicide and the management of these conditions within prisons. The intent was to determine the themes that need to be addressed when creating a MoC. The High Level Design MoC was completed in April 2018 and the process of detailed design and recruitment of new teams is underway.

Background

The Department of Corrections recently completed two reviews which were precursors to the Intervention and Support Project. Jones’ (2017) review of Suicide in New Zealand Prisons 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2016 and Alleyne’s (2017) preliminary review entitled Transforming intervention and support for at-risk prisoners were used to underpin the Intervention and Support Project. Alleyne’s (2017) review revealed that Corrections is managing more people with mental illness than ever before and recommended that a new MoC be developed to improve the intervention and support to people with self-harm and suicidality. Alleyne’s review supported that workforce development, screening, multi-disciplinary teams, social connections, improved physical environments and prison culture should all be addressed collectively to improve prisoner mental health and well-being outcomes.

From an international context, the WHO report Preventing Suicide in Jails and Prisons (2007) stated that work is required to reduce suicide and increase mental well-being in prisons. The report recommends that prisoners should receive the same level of health care as they would receive in their wider community. In acknowledgment of this, the project team looked at how to use evidence-based best practice in the provision of mental health care in New Zealand’s prison system.

Self-harming behaviour in New Zealand prisons: a review of the data

Deliberate self-harm is the term given to a range of behaviours where people try to hurt themselves on purpose but do not intend to die. The major point of difference between suicide attempts and self-harm is the intent to die.

The project team reviewed the data and identified trends in self-harming behaviour in New Zealand prisons. While there has been exploration around suicide, there is less research around self-harm in correctional settings. It is estimated that for every suicide there are 60 incidents of self-harming behaviour (McArthur, Camilleri & Webb, 1999). The 39 deaths, believed to be suicide, between 2010 and 2016 (Jones, 2017) led the project team to consider that there may have been 2,340 instances of self-harm within New Zealand prisons during the same timeframe. A review of the Corrections Integrated Offender Management System (IOMS) for the same period showed 2,051 reported instances of self-harm, which reflected the estimated findings reasonably closely.

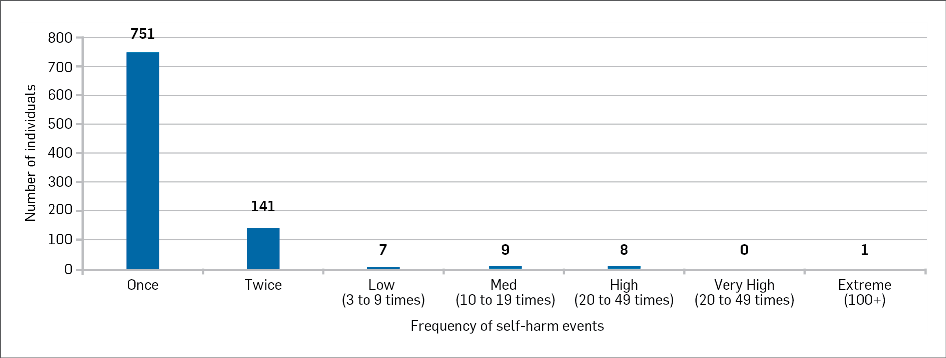

In New Zealand, the number of prisoners who engage in self-harm has remained stable with minor fluctuations from year to year. However, the number of times each individual engages in self-harming behaviour varies dramatically. The majority of reports involve an individual with a single self-harming event, significantly dropping for those who self-harm twice. At the extreme end of the scale, one single individual was responsible for 103 reports of self-harm between 2010 and 2016.

Figure 1: Frequency of prisoner self-harming 2010 and 2016 (From COBRA)

The number of reported instances of self-harm peaked in 2011 and declined in 2013 and 2014. Since 2014, reported occurrences have been steadily rising. Remand prisoners, newly sentenced prisoners, and prisoners new to prison are at increased vulnerability for suicide and self-harming behaviour. It should be noted that the prison population rate is increasing at a much faster rate than the reported self-harming rates.

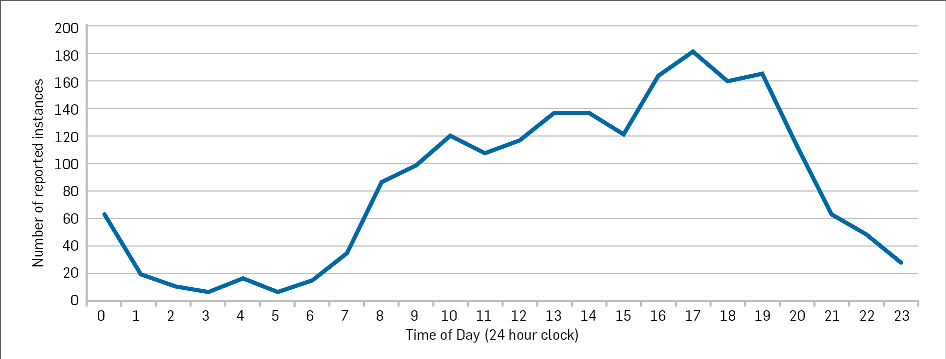

A review of the time of day of reported self-harm incidents showed most instances occurring during daylight hours, with less occurring overnight. This was at odds with international literature highlighting night-time as a high risk period.

Figure 2: Reported instances of self-harm in New Zealand prisons by time of day (From COBRA)

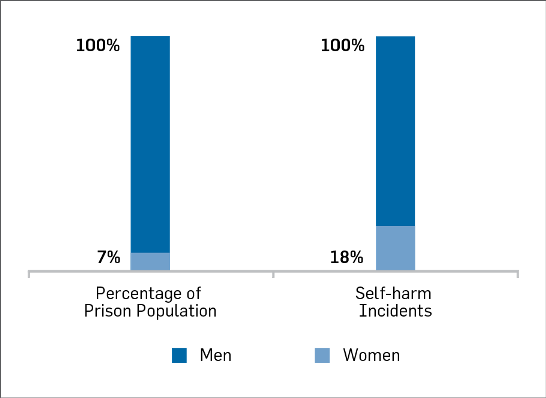

Female prisoners are overrepresented in the statistics. Women make up 7% of New Zealand’s prison population but account for 18% of the reported self-harm instances.

Figure 3: Self-harm Incidents: Comparison between male and female prisoners between 2010 and 2016 (From COBRA)

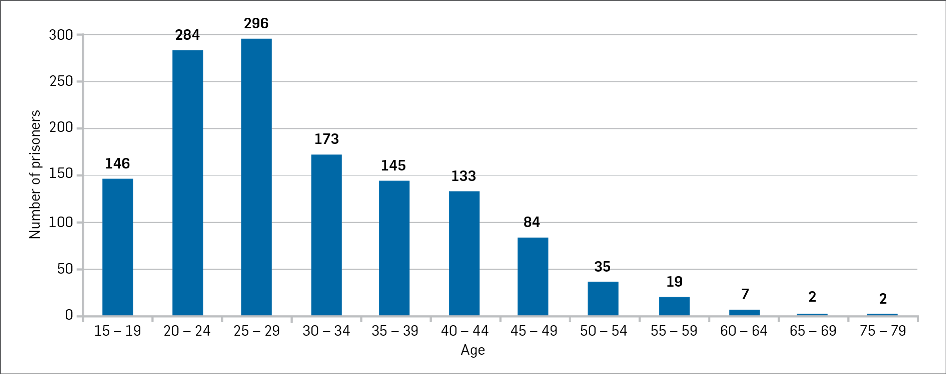

Age is also a factor, with the majority of self-harmers in New Zealand prisons aged between 20-29 years.

Figure 4: Number of self-harm events by age between 2010 and 2016 (From COBRA)

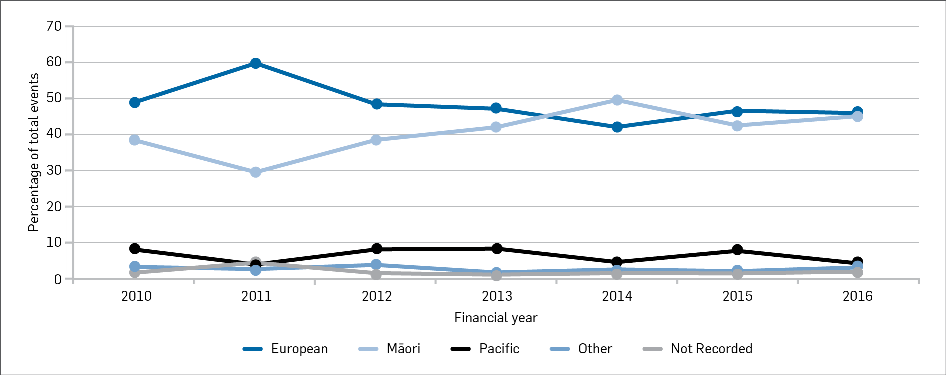

There are differences in the rate of self-harming by ethnicity, with the gap between European and Māori decreasing. While the data shows we have a higher percentage of Māori in the prison population, the instances of self-harming behaviour are less for Māori but trending slightly upwards (compared to their European counterparts).

Figure 5: Percentage of self-harm incidents between 2010 and 2016 by ethnicity (From COBRA)

A review of offender cell/prison movements shows that the average number of cell movements is higher for people who self-harm than people who do not self-harm. The average number of prison transfers is also higher for people who self-harm, as is the number of unit transfers within a prison. Prisoners who self-harm transfer between units and between prisons at a rate double that of those who do not self-harm. While we cannot infer causality from this data, there would appear to be a connection between self-harming behaviour and cell movements.

These findings regarding ethnic and cultural diversity, age, gender, as well as prisoner classification will be taken into account by the project team in the development of the detailed design of the MoC.

International review of literature and guidelines

The project team carried out an international literature review to examine strategies that reduced distress, self-harm and suicide in prisons and correctional settings. The results validated Alleyne’s (2017) review findings that the following areas warrant attention:

- workforce development

- screening

- multi-disciplinary teams

- social connections

- improved physical environments

- prison culture.

Some additional themes also emerged which included:

- use of a “stepped care approach” in the treatment of mental health issues

- the importance of mental health triage

- individualised care plans

- increasing prisoner resilience and health literacy

- reducing stigma around mental illness

- increased information sharing pathways.

In addition, the evidence suggested that being placed in custody can exacerbate mental health difficulties (Plugge, Byng, Bentley, Moore, Czachorowski, McColl & Jones, 2016) and heighten the risk of those who are susceptible to self-harm and suicide. This suggests that greater emphasis is required on the prevention of mental illness in prisons, to ease future pressures on the individual, whānau, prison systems and society as a whole.

Australian research highlighted a novel approach to the issues around suicide in a series of articles named A Situational Approach to Suicide Prevention (Ashfield, Macdonald & Smith, 2017). The authors suggest society needs to approach suicide awareness and prevention from a social perspective (as opposed to emerging from a sole focus on mental illness) in order to achieve better outcomes. Their studies support that situational or psychological distress are predominant in completed and attempted suicides and that to work towards identifying this distress, rather than solely searching out mental illness would be a more effective strategy.

The above article illustrates that the language services use may discourage people from seeking and offering help; that communities will not make it their business to seek or work with mental illness, as it is seen as the responsibility of health professionals. Alternately, these communities may find supporting someone with a mental health “difficulty” more achievable. This perspective on the situational factors that can lead to suicide seeks to normalise distress at life events. It acknowledges at times there will be professional help and medication required but not to the global extent we have now. This series of articles suggest that society has a tendency now to equate distress with signs of mental illness when in fact this may not always be the case. The project team endorse these findings and recognise that identifying psychological distress as well as mental illness, previous and current self-harm and “risk to self” history is of paramount importance in the prison setting.

“At risk” units: Interviews with staff and prisoners

The project team visited nine prisons between August and December 2017. During these visits semi-structured qualitative interviews and informal discussions took place. These interviews included custodial staff, health centre staff, forensic mental health staff and a range of prisoners (remand, convicted, male and female). The purpose of the interviews was to discuss “at risk” units (ARUs), their operating procedures and ways in which Corrections could improve the delivery and quality of care.

Prisoners described screening processes for suicidality and mental illness as archaic and a “tick box” exercise that is easy to “fake”, having learned how to answer the questions so as not to identify as “at risk”. These prisoners believed that admitting to suicidal ideas would weaken them in the eyes of other prisoners and brand them as “mental” or “psycho”, leaving them more vulnerable than before the disclosure.

If placed in an ARU, prisoners were divided over the need for anti-ligature bedding and clothing. In general, prisoners understood the need for the anti-ligature gowns (to keep them safe) but all of the prisoners interviewed considered the gowns to be uncomfortable, ill-fitting and dehumanising. Prisoners could also understand the initial removal of underwear, whilst in the high risk anti-ligature cells. However, for female prisoners in particular, this was found to be excessively humiliating.

Prisoners proposed that having trained mental heath professionals working at reception with staff to complete the “at risk” screening assessments would enable more detailed, knowledge-based interviews resulting in increased quality of information and engagement.

Once placed in “ARUs”, prisoners said they were extremely bored, saying in hindsight they would have been better off not declaring themselves “at risk” or suicidal, where they are stripped of their belongings and placed in a bare cell with no TV and nothing to do.

“No activity is bad. You can't occupy a fragile mind. You need something to do both in the At Risk Unit and in general population. If you weren’t mad when you went in you would be when you came out; staring at four blank walls with nothing to do for 23 hours a day!”

Prisoner A, Rimutaka Prison

Prisoners also reported that exercise and the ability to undertake work were important aspects to address in their recovery that they had no access to currently in ARUs.

“Being able to work would help. It means a lot to me, the thought that I am giving back to society when I work. It wouldn’t work for everyone but it makes me feel good about myself.”

Prisoner B, Rimutaka Prison

Prisoners also described the importance of hope and how lack of hope for the future made life seem desolate. One prisoner recounted how, through art and sewing, he was able to hope for the future. Every night he would lie in his cell and plan what he would draw and sew the next day. It was the hope of creativity that gave meaning to his life and helped him work through suicidal ideation. He recounted how, whilst in the ARU, he was unable to draw or sew because he’d had all articles taken from him. This removed his only hope.

Model of Care

A MoC describes the way health services are delivered. It outlines best practice in care and services for a person as they progress through stages of health or illness (Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2013).

The Intervention and Support MoC was created using the principles of the United Kingdom National Institute of Care Excellence guidelines (2017), which provide the highest level of clinical based evidence. The use of a “stepped care approach” (Ho, Yeung, Ng & Chan, 2016) was chosen to underpin the process as it allows for a smooth transition between levels of intensity of treatment. This approach also allows resources to be pooled together to target care where and when it is required.

The new MoC will “dovetail” with current services (i.e., primary mental health delivered by health centre nurses, medical officers, mental health clinicians and forensic mental health services) to create new ways of working with staff and external agencies that support people reintegrating and engaging with community health providers. The MoC will introduce Intervention and Support Practice (ISP) teams to be based at the three pilot sites. These multi-disciplinary teams will be comprised of mental health and cultural assessment professionals, who will screen, assess and treat people with moderate to severe mental health conditions (including self-harm and suicidality) and provide services for those people who do not fit the “mild to moderate” cohort and are below the threshold for criteria for forensic mental health services. The MoC can be conveyed through the following themes:

Screening and assessment

Reception risk and mental health screening tools are being reviewed for sensitivity, specificity and suitability. The newly created ISP teams will carry out mental health triage and intake assessments. Addiction withdrawal support and cultural assessment will be incorporated into these assessments as required. Support for a prisoner identified as vulnerable to self-harm or suicide will be identified and treatment accessed using a “stepped care approach” adjusting the level of intervention and support as their needs change. Part of the outcome of the intake assessment will be referral to other providers as appropriate, e.g. primary mental health, social work, psychology or forensic mental health services.

Stepped care

The UK Royal College of Psychiatrists recommends a “stepped care” approach to mental health care allowing earlier access to services for people at risk of self-harm and suicide (Georgiou et al., 2016). Although there is evidence that not all people who suicide are mentally ill, a “stepped care” approach to mental health assists in starting dialogue with people about their social connections, mental health, stressors and coping strategies. The “stepped care” approach acknowledges that people have the ability to manage their own health and well-being and it is the role of health services to coach people to grow this ability. It can be argued that health services should not be alone in this task and that social and government agencies have a part to play in supporting this. This would appear to be in keeping with the previously mentioned situational approach to suicide prevention where it is argued that society as a whole has a part to play in preventing suicide in communities.

In its infancy, the “stepped care” approach described pathways in primary care for people with depression and anxiety, but it has been shown to work in many areas of mental health (Ho, et al, 2016). A “stepped care” approach to mental health services will support the right level of intensity of services, in the right place, at the right time, by the right people.

Individual Care Plans

Individual Care Plans will be tailored to the needs of the prisoners, and will be developed using the Intervention and Support Decision-making Framework. This framework will provide guidance on how to identify and manage specific risks, including best unit placement, clothing, bedding, and access to activities. Management of people vulnerable to self-harm or suicide in mainstream units with appropriate support will be the preferred option. The ISP team will consult with the patient and the multi-disciplinary practice team (e.g. custodial staff and case managers) and will review the individual’s needs on an ongoing basis with adjustment to the Individual Care Plan as their needs change.

Individual Care Plans will also take into account the small number of prisoners who require a more intensive care plan. These plans will cater for the very complex cases and involve a greater level of multi-agency coordination and input.

Multi-disciplinary practice

The project team has investigated accountability pathways in multi-disciplinary practice and from this work developed guidelines for Multi-Disciplinary Practice (MDP) within prison settings. These guidelines will address membership, operating structure, identify roles and accountabilities for members, and outline a clear decision making process. Cultural assessors and other specialised supports will be included as part of the MDP approach to address the needs of the individual.

A strong emphasis will be placed on multi-agency partnerships, in particular between Corrections and forensic mental health services. This is to ensure that problem behaviours that shift between active mental disorder and personality disorder do not go unaddressed by virtue of failing to meet threshold criteria at a given time.

Intervention and Support Units

ARUs will become Intervention and Support Units (ISUs). The project team investigated therapeutic environments in the context of mental health, self-harm and suicide in prisons. Therapeutic environments refer to physical, social and psychologically safe spaces that are designed to be healing (Eliassen, Sørlie, Sexton & Høifødt, 2016). With ISUs, it refers to the physical environment and the manner in which we will conduct the business of mental health services, not only in our ISUs, but in prisons overall. There is acknowledgment in international literature of the need for correctional services to be transformed into “psychologically informed, planned environments” (Bantjes, Swartz & Niewoudt, 2017) with therapeutic communities that target specific behaviours in an attempt to bridge gaps between therapy and custody.

The project team will work with ISU staff to identify areas that can become therapeutic spaces incorporatingsensory modulation techniques that reduce distress. For example, techniques may include access to nature/plants, wall murals, bean bags, pet therapy and sensory trolleys.

It is envisaged the ISP teams will work in ISUs alongside custodial staff, giving ready access to professional and multi-disciplinary mental health support. It is planned that with the enhancement of the physical environments there will also be more opportunities for prisoners in ISUs to engage in meaningful activities, to get out of their cells, and to socialise with each other.

The use of anti-ligature bedding and clothing in ARUs and the restriction of articles “in cell” are currently being investigated for comfort, safety and suitability with the intention of improving the patient experience in this area.

The project team identified an opportunity in ARUs regarding the ability to mix prisoners with different security classifications. Currently, prisoners with different security classifications cannot mix, however, in some cases this could be done safely in the ARUs. An exemption is being sought to address this issue, allowing more “out of cell time” for people. This will encourage social connection and assist in reducing suicidal ideation and psychological distress.

Prisoner resilience

To build prisoner resilience, the project will introduce mental health literacy programmes. Prisoner peer support programmes and listener schemes are also being investigated. Evidence shows these programmes can be very helpful to distressed and suicidal people in custody. Care will be taken to ensure adequate supports and clear boundaries are in place allowing peers to carry out their duties in an appropriate and safe manner.

Collection, storage and sharing of data

The legal parameters of information-sharing protocols between health and custody will be further examined. The intention is to create safe information-sharing pathways that benefit the patients and recognise that custody staff require limited health data to support and inform care.

Preparing for the change

The MoC is a transformational change in practice for Corrections. In recognition of the size and scale of the change, support will be provided to pilot sites through change management activities. This will include targeted communications and training to prepare staff for the implementation of the new MoC and support to successfully embed it into business as usual practice. In preparation for this, the provision of staff training, staff capability and current training have been reviewed in the context of mental health and suicide awareness.

Corrections officers currently receive around 7.5 hours introductory training in suicide awareness; this includes how to conduct “at risk” assessments. Subsequent suicide awareness refresher training is 4 hours every two years. Currently, there is no specialised training or necessary staff qualification for staff to work in an “at risk unit.” Staff recruitment and selection guidance is provided by Human Resources for High Risk Units and within this, for ARUs. The future plan will see all frontline staff receiving an introduction to mental health training with updated suicide awareness training. This will support staff in identifying and managing psychological distress with a view to reducing self-harm and suicide. Further specialised mental health training will also be provided for ISU custody staff. The introduction of professional supervision for custodial staff working in ISUs will also promote best practice in this area.

What’s next?

The new MoC will be introduced at three pilot sites: Auckland Prison, Auckland Region Women’s Correctional Facility and Christchurch Men’s Prison. At the time of writing (May 2018) the ISP teams are being recruited. Following evaluation, the new MoC will be rolled out nationally.

The project team is currently working on the detailed design of the MoC, including:

- reviewing the use of current screening tools

- developing mental health triage and intake assessment procedures

- outlining what a therapeutic environment looks like in the prison context

- working with our key stakeholders, including Māori services, to ensure the detailed design is responsive to culture, age and gender.

Transforming Intervention and Support for People in Prison Vulnerable to Suicide and/or Self-harming Behaviour

Conclusion

The project team undertook a series of reviews of local and international evidence based practices to reduce self-harm and suicide in prisons. This included input from frontline staff and prisoners.

This work allowed the team to create a MoC for the delivery of prison-based mental health services in New Zealand prisons with the intention of reducing self-harm and suicide. The new MoC will be piloted at three prison sites, evaluated, and introduced to all prisons over time.

It is acknowledged that Corrections staff save lives every day, and work with many complex, troubled people in custody. The MoC will allow staff more flexibility to treat distressed prisoners as individuals with different needs. The model proposes that at times vulnerable prisoners can be supported in mainstream prison environments and that least restrictive practice will be more therapeutic for people’s mental health in the long term. The model also supports an increase in therapeutic physical environments not only in ISUs but in the wider prison environment.

Corrections has a great opportunity to improve mental health and wellbeing for all people in custody in New Zealand The introduction of the new, whole of prison MoC will support a community of change in making mental health, self-harm and suicide everyone’s business.

References

Agency for Clinical Innovation (2013).Retrieved from https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/181935/HS13-034_Framework-DevelopMoC_D7.pdf#zoom=100

Alleyne, D. (2017). Transforming intervention and support for at-risk prisoners. Practice. The New Zealand Corrections Journal, 5, (2) p33-39.

Ashfield, J., Macdonald, J., Smith, A. (2017). A situational approach to suicide prevention.

Bantjes, J., Swartz, L., & Niewoudt, P. (2017). Human rights and mental health in post-apartheid South Africa: lessons from health care professionals working with suicidal inmates in the prison system. BMC International Health & Human Rights, 171-9. doi:10.1186/s12914-017-0136-0

Eliassen, K., Sørlie, T., Sexton, J., & Høifødt, S. (2016). The effect of training in mindfulness and affect consciousness on the therapeutic environment for patients with psychoses: an explorative intervention study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(2), 391-402.doi:10.1111/scs.12261

Georgiou, M., Souza, R., Stone, H., & Davies, S. (2016). Standards for Prison Mental Health Services – Second Edition Quality Network for Prison Mental Health Services. Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Ho, Y., Yeung, F., Ng, T. H.Y., Chan, C. S. (2016). The Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of “Stepped Care” Prevention and Treatment for Depressive and/or Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Scientific Reports, 6, 29281. http://doi.org/10.1038/srep29281

Jones, R. (2017) Suicide in New Zealand Prisons - 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2016 Practice. The New Zealand Corrections Journal, 5, (2) p26-32.

McArthur, M, Camilleri, P, Webb, H (1999). Strategies for Managing Suicide & Self-harm in Prisons. Trends & Issues in Crime & Criminal Justice. Aug1999, Issue 125.

National Institute of Clinical Excellence. (2017). Mental health of adults in contact with the criminal justice system. NICE Guideline.

Plugge, E., Byng, G., Bentley, C., Moore, P., Czachorowski, M., McColl, A., Jones, D. (2016). Rapid review of evidence of the impact on health outcomes of NHS commissioned health services for people in secure and detained settings to inform future health interventions and prioritisation. Public Health England. Retrieved from www.gov.uk/phe

World Health Organisation and International Association for Suicide Prevention. (2007) Preventing suicide in jails and prisons. Department of Mental health and Substance