Evaluation of brief methamphetamine-focused interventions

Jill Bowman

Principal Research Adviser, Department of Corrections

Author biography:Jill joined the Department of Corrections’ Research and Analysis Team in 2010. She manages a variety of research and evaluation projects and has a particular interest in the outcomes of released prisoners, issues relating to alcohol and drugs, and the needs of female offenders. As well as working for Corrections, she volunteers at Arohata Prison, teaching quilting to the women undertaking the drug treatment programme.

Introduction

Research by the Department (Indig, Gear and Wilhelm, 2017) identified that over half of New Zealand prisoners (56%) had used methamphetamine at some time during their lives and, of these, 58% indicated they had used it in the year before coming to prison. Over a third of prisoners (38%) had abused methamphetamine (that is, its use had caused problems in their lives) or had a dependency over their lifetimes; over the preceding 12 months, 16% of prisoners had a methamphetamine abuse disorder (3%) or a dependence disorder (13%) [1].

Compared with prisoners without a methamphetamine dependence disorder, prisoners with a lifetime dependence disorder were nearly twice as likely to display comorbidity with either another substance use or mental disorder.

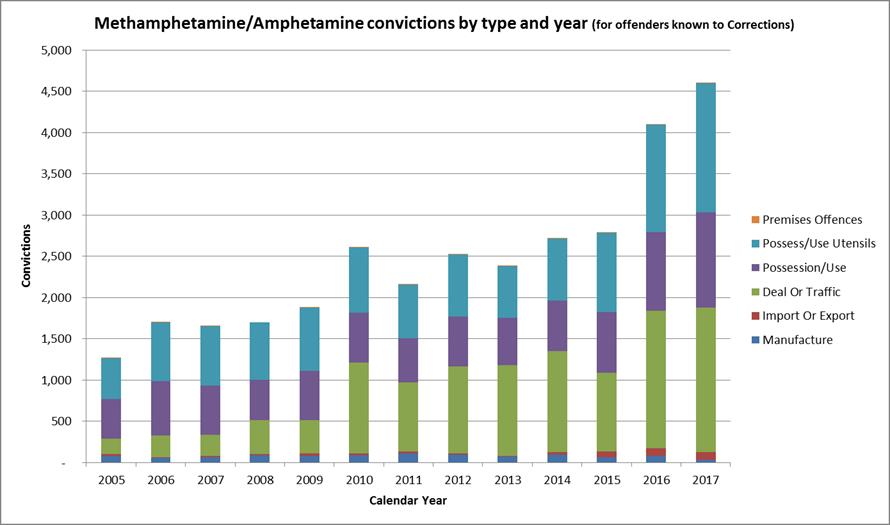

More recent analysis of administrative data by the Department suggests that the proportion of prisoners who have used methamphetamine is higher than that found by Indig et al, and the number of convictions for amphetamine/methamphetamine-related offending for offenders known to Corrections has also increased steadily over the last 12 years (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Methamphetamine/Amphetamine convictions by type and year (for offenders known to Corrections)

Because of the high level of methamphetamine use amongst New Zealand prisoners, the Department has introduced a number of interventions (financed by the Proceeds of Crime Fund) to assist prisoners to reduce or cease its use.

In September 2017, two interventions were introduced as pilot programmes at Mt Eden Corrections Facility (MECF), a prison which predominantly houses persons remanded in custody. The interventions are: screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT), and a group-based methamphetamine-specific programme “Meth and Me short course” [2]. SBIRT is an approach to delivering early intervention and treatment services to individuals at risk of developing, or who have developed, substance use disorders (SAMSHA, 2011). Its purpose, at Mt Eden, is to identify AOD use (specifically methamphetamine) and increase participants’ motivation to reduce their substance using behaviours.

“Light-touch” motivational interventions of this nature sit on a continuum of AOD services available to prisoners. Prisoners who complete these initial programmes can be expected to become more willing to engage with intensive programmes, such as the six-month Drug Treatment Unit (DTU) programme. In the 2017/18 year, around 1,100 prisoners commenced a programme in one of the Department’s DTUs. In the 2018/19 year, the Department plans to establish two new DTUs and scale up other intensive drug treatment programmes. This is expected to cater to an additional 600 people a year.

Newly received prisoners who agree, are assessed for their level of risk (low, moderate or high risk of health, social, financial, legal and relationship problems) associated with their use of methamphetamine (as well as other drugs and alcohol), using the ASIST[3] screening tool. Those who are identified as using methamphetamine are given a brief intervention immediately by the assessor. This consists of a motivational discussion on the risks and negative consequences of substance use, and advice, plus options for modifying drug use. Those who require a greater level of intervention than that provided by the brief intervention and educational material are then referred to treatment – a brief treatment programme for those with less severe substance use disorders and specialised treatment for those with more severe substance use disorders.

The methamphetamine intervention to which participants at MECF may be referred is the “Meth and Me short course”. It comprises two two-hour group-based psycho-education sessions and is delivered over consecutive days. The purpose is to provide information to participants about the effects of meth use, withdrawal symptoms and strategies to manage cravings and risky situations, along with relapse prevention strategies. (A longer form of Meth and Me is delivered as part of the drug treatment programmes at Auckland Prison, Spring Hill Corrections Facility and Christchurch Men’s Prison.)

SBIRT and Meth and Me are delivered by Odyssey House Trust, a not-for-profit organisation that delivers programmes to help people overcome alcohol, drug and gambling addiction problems. Odyssey is contracted to deliver the interventions until June 2019.

Aim of the evaluation

The purpose of the evaluation was to understand the value to participants of SBIRT and the Meth and Me short course and the impact they had on their motivation to reduce or eliminate their drug use (particularly methamphetamine). Depending on the evaluation findings, consideration will be given to introducing the programme in other prisons for remand prisoners.

Evaluation methodology

The evaluation comprised qualitative and quantitative components. Fourteen men who had participated in the interventions, plus two facilitators, were interviewed at MECF between 20 and 22 March 2018. The men were selected for interview from all those who had completed the two interventions in February. Men who’d completed fairly recently were chosen to improve the likelihood they’d remember the course material, and to minimise the chances that they’d been moved to another prison or released. As well as being questioned about the interventions, the men were asked about their meth use prior to their imprisonment, alcohol and drug programmes previously undertaken, and their intentions about ceasing meth use on their release, to provide context for their responses about the programmes. In addition, administrative data collected about participants in SBIRT and Meth and Me between implementation in September 2017 and the end of February 2018, was analysed.

Key findings

The two interventions were generally regarded positively by the participants who were particularly complimentary about the facilitators. Most of the men were not surprised by their ASIST results, and they found the subsequent discussion and the information they were given about treatment options useful. However, there was a tendency for participants to be preoccupied with their immediate needs resulting from being remanded in custody, including whether residential treatment options existed to which they could be bailed. Their thinking about longer term treatment choices tended to be vague.

The men were enthusiastic about participating in Meth and Me. Although most said they were already familiar with the content presented in the intervention, they did recall some things that had surprised them, or were notable for personal reasons. The programme had allowed some of the men to understand the impacts meth was having on their lives and to realise the reasons why they were behaving as they were under the influence of meth (rather than thinking it was “just them”). They were particularly fascinated by the effects meth had on their brains, including the massive release of dopamine after taking meth. Other things they found useful were: understanding the broader health effects of meth and the ability of the body to repair itself, advice about asking for help, ways of keeping themselves occupied, and alternatives to using meth or other drugs in dealing with difficult situations.

All said they had decided prior to participating in the interventions to give up meth, with most citing their children as their primary motivation. A commonly expressed view was that they were sick of the lifestyle and tired of coming to prison. However, despite covering relapse prevention in the final session of Meth and Me, no participants had completed a relapse plan and none had thought about concrete steps they would take to avoid meth use in future. Their plans were fairly simple, such as a desire to move somewhere else (including overseas), avoiding meth-using friends, finding work to alleviate boredom, and similarly well-intentioned but imprecise ideas. The feasibility of their plans and the practical steps needed to implement them had not been thought through – including, for example, whether their convictions would preclude a move overseas.

Some men expressed interest in further drug treatment. However, facilitators tended to offer information about community programme options, omitting to mention the drug treatment programmes in prisons. The Department has reminded the provider of these programmes as an option for people sentenced to a term of imprisonment.

While some men would have liked a longer programme to enable the discussion of content in more depth and to allow more interaction between participants, others thought it was long enough, and the realities of a remand prison would make any extension difficult.

The providers noted as problematic the practice of assessing newly received men for meth use while those individuals were still under the influence of drugs. However, they had decided it was preferable to include them in the interventions, given the obvious drug problem, rather than risk losing the opportunity to help them. Other issues they identified included the requirement to record participation data manually and in multiple locations, which they feared meant increased likelihood of errors. It was also noted that men potentially underreported their alcohol and drug use as they were concerned about the confidentiality of the assessment results.

The numbers completing SBIRT and Meth and Me were lower than anticipated. However, this was not unexpected for a pilot programme, which is testing how a model might work in practice. In addition, there are a number of unique challenges in operating a new programme in a remand prison. These include the high turnover of people on remand, the competing priorities of new remandees (for example, meetings with lawyers, meetings with staff, and families visiting), the allocation of assessment and programme space, and the availability of staff to escort people to programmes. The Department is working with site staff and the provider to overcome the issues identified.

Conclusion

SBIRT and Meth and Me, although light touch interventions, generally appear to achieve the outcomes expected.

SBIRT has been successful in:

- identifying AOD problems in newly received offenders in prison

- raising awareness of substance use issues with men identified as having AOD problems

- referring those who have used meth to the Meth and Me intervention (as well as providing information about other treatment options).

Meth and Me effectively provides information to participants about the effects of meth use, withdrawal symptoms and strategies to manage cravings and risky situations, along with other relapse prevention strategies. The majority of participants were able to recall a good proportion of the content covered in the course, and reported having found it useful. Consequently, there are grounds for expecting that a significant proportion of participants who complete this motivational programme will, if their ensuing sentence length allows it, go on to participate in a more intensive AOD programme.

The evaluation recommended that consideration be given to introducing SBIRT and Meth and Me into other prisons, including – with appropriate modifications – the women’s prisons, and extending it more widely for people on remand.

[1] Simply put, abuse reflects “too much, too often” and dependence is the inability to cease methamphetamine use.

[2] Chester, 2018 provides information on the implementation of SBIRT and Meth and Me at MECF.

[3] The Alcohol and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASIST) assesses the level of risk associated with alcohol and drugs, including methamphetamine. The version used on prisoners has been modified from the original developed by the World Health Organisation, and it is intended to be administered to all prisoners.

References

Chester, C. (2018) Early intervention and support: Corrections’ Methamphetamine Pilot – Practice, The New Zealand Corrections Journal, Vol 6, Issue 1, 33-36, Department of Corrections

Indig, D., Gear, C. & Wilhelm. K., (2017) Impact of stimulant dependence on the mental health of New Zealand prisoners, Department of Corrections, 2017.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) (2011). Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in Behavioral Healthcare. Accessed at https://cms.samsha.gov/sites/default/failes/sbirtwhitepaper_0.pdf