Inside probation officer contacts: A summary of an analysis of recorded probation

Darius Fagan

Chief Probation Officer, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Darius Fagan has worked for the New Zealand Department of Corrections since 2001. He started his career as a probation officer and believes in the important role probation officers can play in helping offenders change their lives. Darius is passionate about designing practice that adheres to evidence-based concepts that can be applied by probation officers in their day-to-day work.

Introduction

More than 30,000 offenders are currently completing community-based sentences in New Zealand[1], with most of them managed by a probation officer. Probation officers are responsible for ensuring compliance with sentence conditions, organising referrals for rehabilitative programmes, and working with offenders to target their relevant risk and protective factors through various brief interventions and interpersonal techniques. Probation officer practice is rooted in the principles of Risk, Need, and Responsivity (RNR; Andrews, Bonta, & Hoge, 1990). According to these principles, probation officers should spend more time with high risk offenders, focus on relevant risk and protective factors, and work with offenders in a way that is suitable for their learning style.

Up until ten years ago, little was known about the effectiveness of probation officer practice and how well it adhered to the RNR principles. Bonta, Rugge, Scott, Bourgon, and Yessine (2008) were one of the first to critically evaluate probation officer practice in Canada by examining audio recordings of sessions with probation officers and offenders. They found overall poor adherence to the RNR principles, as probation officers tended to focus on compliance rather than criminogenic needs and most did not demonstrate skills that would contribute to a positive behaviour change (e.g. prosocial modelling). They concluded that these issues are likely to be common to many probation centres and that more training and supervision is required to ensure that probation officers target their sessions on relevant risk factors using appropriate techniques.

In 2015, the Department of Corrections conducted the first study critically evaluating probation practice in New Zealand.[2] This study evaluated how well probation officers were adhering to the RNR principles by observing 81 video recordings of their sessions with offenders and comparing this to how they have been trained to use RNR in practice. It analysed the content of discussions and the skills that were employed by probation officers, such as motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioural techniques. Overall, this study found that probation officers spent more time discussing relevant risk and protective factors than sentence conditions or compliance. They demonstrated good relationship building skills, and some evidence of motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioural skills. Furthermore, probation officers did not engage in explicit session structuring and demonstrated inconsistencies when delivering brief interventions, with many indicating an intervention was delivered when it was not observed by the researchers. This discrepancy may have been the result of varying perceptions between probation officers and researchers regarding what actions are sufficient to be considered a brief intervention.

This study in 2015 concluded that, overall, probation officers were adhering to the RNR principles to a moderate degree. It was recommended that probation officers should be observed and supervised more regularly, that they should focus on one criminogenic need per session, and that more structuring of sessions was needed. As it was the first critical evaluation of probation practice in New Zealand, these findings were helpful in providing an insight into practice, which could be used to guide future changes in probation officer training and supervision.

Although the practice model has remained the same, several changes have been made to probation practice since the 2015 study. Motivational interviewing has been the biggest focus of training in the last two years to encourage positive attitude and behaviour changes. Other changes include an enhanced focus on mental health and suicide awareness, working with youth and Pasifika clients, using the alcohol and drug screening tool known as ASSIST (Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test), developing offence pathways and relapse prevention plans, and developing an increased focus on employment and education. The Department also updated its probation officer toolkit for brief interventions to make it more accessible and to provide information on what tools to use for which risk factor.

The current research aimed to evaluate probation practice by examining what is being discussed during report-in sessions, what skills are being employed by the probation officer during the session, and how well they are adhering to the RNR principles. Furthermore, it evaluated the results in comparison to the findings of the 2015 study to see how practice has changed since then, and whether these changes reflect the new training targets that have been implemented by the Department.

Results

Session length and frequency

A total of 16 hours and 34 minutes of session recording was received. The average length of a recording was 20 minutes, ranging from four minutes to 50 minutes. A significant number of recordings started or ended abruptly or referred to something discussed outside of the recording. These recordings were still included in the analysis, but it meant that some items could not be coded, such as the opening or closing of the session.

As most offenders were part way through their sentence when coding was being completed, the relationship between an offender’s risk and the number of sessions attended during their sentence was not able to be calculated. This meant that probation officers’ adherence to the risk principle (i.e. devoting more time to higher-risk offenders) was not able to be assessed.

What was discussed in the sessions?

On average, 64% of the time in sessions was spent discussing risk and need factors identified by the Dynamic Risk Assessment for Offender Re-entry (DRAOR) tool. An average of 7.5% of sessions was spent discussing sentence conditions or compliance. The remaining time unaccounted for was mostly spent on organising the date of their next session, discussing enrolment in programmes, and filling out necessary forms related to the management of their sentence. Some remaining time was also spent discussing unrelated factors such as the offender’s physical health or events and circumstances in the lives of their family and friends.

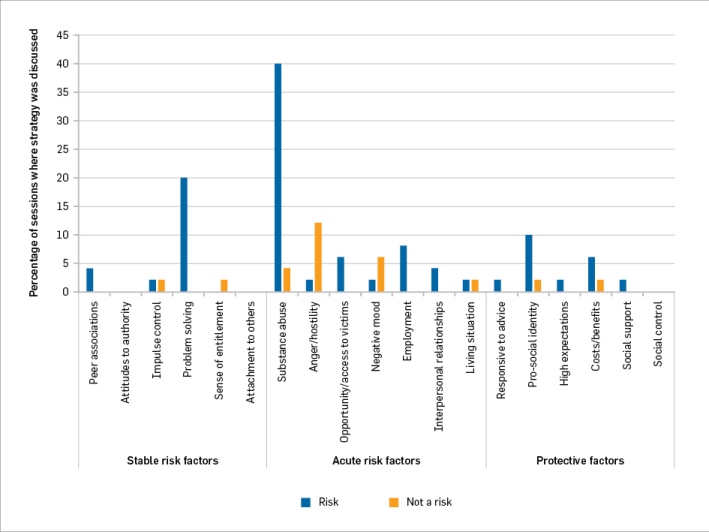

Percentages were also calculated for how often individual DRAOR factors were discussed; these are shown in Figure 1. Overall, acute factors were discussed more frequently than stable or protective factors. The four factors that were most discussed include substance abuse (noted in 72% of sessions), interpersonal relationships (72%), and employment (64%) from the acute subscale and problem solving (60%) from the stable subscale. Just under half of sessions discussed opportunity/access to victims (46%) and living situation (46%) from the acute subscale and social support (44%) from the protective subscale.

Factors that were least frequently discussed include responsiveness to advice (8%) and social control (16%) from the protective subscale, and sense of entitlement (10%) and attitudes towards authority (16%) from the stable subscale. This demonstrates that overall most sessions focused on practical issues such as employment, relationships, substance abuse, and decision-making processes concerning the offender’s ability to solve problems and handle high risk situations.

Percentages were also calculated for how often strategies to address risk and protective factors were discussed. As Figure 1 illustrates, this was relatively low compared to how many times the factor was discussed. The most frequently discussed strategies were for substance use (44%) and anger/hostility (14%) from the acute subscale, and problem solving (20%) from the stable subscale. Strategies for all other factors were discussed in 12% of sessions or less.

Did sessions focus on needs relevant to individual offenders?

Although the recordings suggest that sessions were relatively brief (average of 20 minutes), Trotter (1996) claims that short sessions can be effective if the time is appropriately used. For this reason, the proportion of sessions discussing relevant and irrelevant factors was calculated. This was done by taking DRAOR scores from the assessment before the recorded session and for each factor noting if it was relevant for the offender (risk factors scored as 1 or 2 and protective factors scored as 0 or 1) or irrelevant (risk factors scored as 0 and protective factors scored as 2) and whether each factor and a strategy to address it was discussed.

This analysis resulted in two proportions: one for relevant and one for irrelevant factors. As discussed in the previous report, if the RNR principles are adhered to, the proportion of relevant factors should be larger than that of irrelevant factors as relevant factors should be discussed more. The greater the difference between the two proportions, the more probation officers are adhering to the need principle.

For all three subscales, factors were discussed more often when they were relevant for the offender, as illustrated in Figure 1. These differences were large for stable (31% vs. 18%), acute (62% vs. 32%), and protective (30% vs. 17%) factors, demonstrating good adherence to the need principle. Almost all factors were discussed more frequently when they were relevant, with only a few exceptions such as attitudes to authority, anger/hostility, and negative mood. This indicates that overall probation officers were doing a good job of discussing topics relevant to the offenders’ risk of re-offending.

Strategies to address factors were discussed more when they were relevant only for stable (5% vs. 3%) and acute (15% vs. 9%) factors, with marginal differences. Strategies to address protective factors were discussed slightly more when they were not relevant (4% vs. 5%), indicating that there is room for improvement to discuss more relevant strategies and better adhere to the need principle. However, this finding may also be due to the overall low prevalence of strategies being discussed in sessions.

As illustrated in Figure 1, probation officers did a good job of discussing strategies concerning peer associations, problem solving, substance abuse, opportunity/access to victims, employment, interpersonal relationships, responsiveness to advice, high expectations, and social support when they were relevant for the offender. Impulse control and living situation showed no significant differences, and strategies to address anger, negative mood, and sense of entitlement tended to be discussed more frequently when they had not been identified as relevant.

Figure 1: Were the strategies discussed targeting relevant DRAOR factors?

Skills and techniques used

The probation officers’ skills in the session were evaluated in relation to four domains: motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioural techniques, relationship building, and session structuring. Overall, probation officers demonstrated good relationship building skills and motivational interviewing skills. Evidence of cognitive-behavioural techniques was mixed and session structuring was limited.

In terms of their motivational interviewing skills, probation officers tended to ask open-ended questions well and endeavoured to reflect the offender’s feelings. They were positive in their approach and often provided praise and positive feedback about the offender’s efforts and abilities. Probation officers often tried to elicit change talk from the offender and tried to get them to come up with their own ideas for achieving personal change. Overall, this demonstrates that probation officers have good skills in motivational interviewing, reflecting the training that has been implemented over the past few years.

However, there is scope for improvement with certain motivational interviewing techniques. More specifically, using summarising throughout sessions (particularly at the end of a session) could be used more. Summarising is important for consolidating what has been discussed and ensuring that the probation officer has understood what the offender has been saying. Furthermore, when offenders engaged in sustain talk (i.e. expressing that they are unable to change or want/need to keep things as they are) probation officers could engage more, thus taking advantage of valuable opportunities to make positive change. Overall, however, motivational interviewing was present.

Although probation officers are not formally trained in cognitive-behavioural techniques, their use of these approaches during sessions was still observed. Interestingly, probation officers were employing certain cognitive-behavioural techniques well, such as prosocial modelling, responding to challenges in a constructive and respectful way, and praising instances of positive thinking or behaviour. However, other cognitive-behavioural techniques (e.g. such as making an explicit link between thoughts, feelings, and behaviour) were largely absent, suggesting that training in this area could be valuable.

Probation officers demonstrated excellent relationship building skills. They came across as friendly, engaged in small talk at the start of sessions, and were polite, respectful, and responsive. They achieved the right balance between maintaining professionalism and being warm and engaging towards offenders, which had a positive effect on rapport and participation. There were no incidents observed where probation officers’ responses might be construed as disrespectful towards an offender’s culture or ethnicity. However, their relationship building skills could be further enhanced by adopting a more focused cultural approach. For example, sessions with offenders who identify as Māori could be used to engage in whakawhanaungatanga[3] and identifying if the offender has any preference for practices they would like incorporated into sessions, such as karakia or waiata.

Probation officers are not explicitly trained in session structuring, however motivational interviewing does incorporate some elements of this through the concept of agenda mapping. Agenda mapping involves the offender and probation officer collaborating to set goals for the session and outline what they would like to discuss. Probation officers have recently learned more about this technique through a new motivational interviewing training package delivered in 2017 and 2018. Better use of agenda mapping could have enabled probation officers to lead sessions more successfully. Session structuring is beneficial, as outlining an explicit plan at the start helps to keep the session focused and relevant to the offender’s risk. Closing sessions with a summary also helps to consolidate what was learned during the session.

Overall assessment of sessions

Overall, probation officers were observed to be focused on encouraging positive behaviour change. They adopted a constructive and responsive approach to work with offenders to make changes rather than focusing on compliance. Furthermore, most sessions were collaborative, giving offenders plenty of opportunities to talk and weigh in with their opinions. Probation officers were also observed to act in a way likely to engage the offender, as demonstrated by their strong relationship building skills. They appeared interested in what the offender had to say and remained respectful and friendly throughout the session.

Finally, the notes in IOMS describing the session tended to be accurate representations of the content of the session. These notes provided sufficient detail about what was discussed, the tools that were used, and the next steps the probation officer was going to take.

Conclusion

This study aimed to evaluate probation officer practice by assessing its adherence to the RNR principles and how this has changed since this research was conducted in 2015. Although adherence to the risk principle was unable to be calculated, probation officers generally showed practice consistent with the principles of need and responsivity. The findings also demonstrated that some of the changes in training are being reflected in practice. Improvement in most areas was observed, indicating that probation officer practice is moving in the right direction. Recommendations have been provided for areas that showed scope for improvement to enhance the effectiveness of sessions with offenders in the future.

[1] Muster information recorded 12 March 2018.

[2] Please refer to this report for a detailed overview of previous literature and probation officer training and practice models in New Zealand.

[3] Defined in this context as the process of making connections and relating to others to establish social bonds.

References

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17(1), 19-52. doi:10.1177/0093854890017001004

Bonta, J., Rugge, T., Scott, T.-L., Bourgon, G., & Yessine, A. K. (2008). Exploring the black box of community supervision. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 47(3), 248-270. doi:10.1080/10509670802134085

Trotter, C. (1996). The impact of different supervision practices in community corrections: Cause for optimism. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 29(1), 1-19. doi:10.1177/000486589602900103